Ordinary Time

Ordinary Time

by Debie Thomas

The other day, my daughter wandered into the room as I was pounding away on my laptop. Frantic to meet a deadline, I barely glanced at her. "I don't know what to do!" she said miserably, collapsing on the couch. "I'm not good at summer. What should I do?" "Do nothing," I said glibly, still typing like a maniac and scattering notecards in twelve directions. "Just be."

She sat up immediately to take in my disaster zone of a workspace, my racing fingers, my disheveled hair. Narrowing her eyes, she responded with the devastating shrewdness of the teenager: "You mean like you?"

Um, yeah kid. Just like me. My children know me well; I am notoriously bad at just being. Just being makes me restless and grumpy. I wallow in guilt, convinced that I'm wasting precious time and accomplishing nothing of value. I much prefer trajectory. Direction. Busyness. I much prefer a point.

As I've written previously in this column, I didn't grow up following the liturgical calendar, so the rhythm of the church seasons is still a novelty for me — a wise, wonderful novelty I'm eager to learn from. But the season we're in right now? The season of Ordinary Time? I'm finding it a bit difficult. A bit counter-cultural. A bit nerve-wracking. If I had a choice (and thank God I don't!), I'd skip it.

"Ordinary Time" derives its name from the Latin "ordinalis," meaning "ordered," or "numbered sequentially." During every other church season, we journey towards a culmination or apex. In Advent, we prepare for the birth of the Saviour. During Lent, we enter the wilderness, our eyes trained on the Cross. On Easter, we scale the mountaintop of the Resurrection. During Pentecost, we await Spirit and Fire — the great birthing of the Church.

But during Ordinary Time? We count Sundays. We count weeks. We order life as best we can. We enter an in-between time, a season unmarked by pageants, pancake suppers, or foot-washing ceremonies. During Ordinary Time, we neither ascend nor descend, neither fast nor feast. We plod along. We just be.

Why does this make me squirm? Is it because I refuse to assign spiritual value to dirty dishes and over-stuffed recycling bins? Because I don't know how to look for God in "regular" places? If I asked you to list synonyms for the word "ordinary," what would you come up with? "Boring?" "Unimportant?" "Insignificant?" I wonder if we even know how to inflect the word positively.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

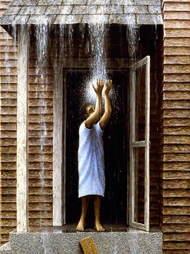

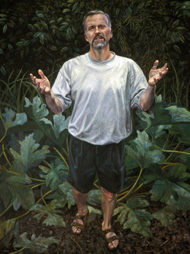

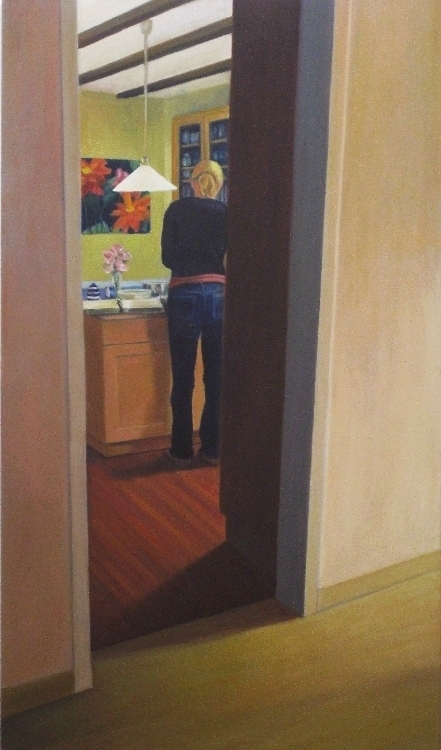

Barbara Lidfors: In the Kitchen (top of the page), Reaching

and Two in the Kitchen

In her book, An Altar in the World, Barbara Brown Taylor describes our world as "so thick with divine possibility that it is a wonder we can walk anywhere without cracking our shins on altars." I love the description, but I rarely believe its claim. To embrace Ordinary Time is to embrace daily life itself — the routines, the chores, the missed appointments, the traffic jams. It is to trust that these mundane pieces of my life are also "altars," imbued with the holy.

The odd and interesting thing is that Jesus did most of his living in "ordinary" time. He spent the first thirty years of his life in quiet obscurity, doing manual labor. Even after his public ministry began, he was bound to the mundane by brutal necessity; in a world without running water, indoor toilets, refrigeration, cars, or computers, there's no way his daily life could have been brisk and efficient. Some scholars estimate that Jesus walked over 20,000 miles during his lifetime on earth. How "ordinary" those miles must have felt along dusty roads, in the scorching heat or the bitter cold. Would he have called them boring? Pointless?

Richard Foster writes that "the discovery of God lies in the daily and the ordinary, not in the spectacular and the heroic." What would it feel like to believe this? I tend to think of mountaintop religious experiences as the most formative ones. But surely, what formed Jesus — what shaped him into the son, the friend, the teacher, and the healer he became — were those long, plodding days of ordinary time. When else would he have gathered, composted, seeded, and harvested the raw materials of his life? When else would he have taken root?

His example makes me wonder what I'm becoming during Ordinary Time. As a wife, a mother, a friend, a writer — am I composting anything? Paying enough attention to turn over and over the rich materials of my life? As I dust furniture, fold laundry, face deadlines, and just be — what is taking root in me?

"Listen to your life," says Frederick Buechner. "See it for the fathomless mystery it is. In the boredom and pain of it, no less than in the excitement and gladness; touch, taste, smell your way to the holy and hidden heart of it, because in the last analysis all moments are key moments, and life itself is grace."

The great gift of Christianity, of course, is that nothing, finally, is "ordinary." Everything in our world — every pause, every mile, every uneventful hour — is shot through with mystery. To notice this is to bend the knee at a strange and beautiful altar. The altar of the extraordinary.

*******

This column first appeared on the Journey with Jesus website, http://www.journeywithjesus.net, for which Bedie Thomas writes a weekly column called 'The 8th Day.' Debie Thomas earned her MA in English Literature from Brown University and an MFA in Creative Writing from The Ohio State University. Her essays have appeared in the Kenyon Review, River Teeth: A Journal of Nonfiction Narrative, and Slate Magazine. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her family.

Barbara Lidfors was born in Iowa and grew up in Minnesota, USA. Her early interest and love for art was influenced by her father, Eugene Johnson, who was a painter, a potter and an art professor at Bethel College in St. Paul, Minnesota. After studying two years at Westmont College in California, Barbara Lidfors returned to Bethel College to earn a B.A. degree in 1971. Further art studies, with an emphasis in painting, followed at the University of Minnesota. In 1982 she moved with her husband, Robert, and children to Germany. http://www.lidforsbarbara.com

*******

For more materials for Trinity Sunday until Advent, click here