England: Churches in Little Walsingham

Churches in Little Walsingham

by Jonathan Evens

The Anglican Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham “occupies an island site in Walsingham, close to the ruins of the original medieval Priory.” The present-day shrine “was gradually created in 1931 from derelict farm buildings and cottages, with a brand-new Shrine Church in the southeast corner of the site.” The shrine, established by Fr. Alfred Hope Patten, has continued to be developed with modern accommodation blocks, refectory, visitor center, gardens, and chapels.

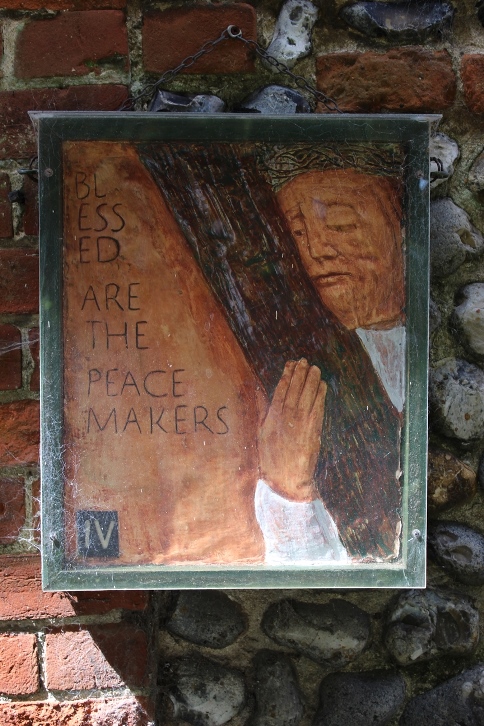

Jane Quail’s beautiful Stations of the Cross were installed in the grounds in 2001 and are much loved by pilgrims. As with the Stations of the Cross by Irene Ogden at St. Julian’s Church in Norwich, this imaginative cycle makes creative textual and visual connections between the events of the fourteen stations and scriptures not normally associated with those events—namely, the Beatitudes. The artworks create a harmonious whole and inspire new connections between scripture passages.

Quail is a sculptor in wood and stone who was born in India, where she acquired an interest in sculpture from an early age. She attended an art course in Durban, Natal, in South Africa and then worked for a time with Canon Ned Paterson, founder of the Cyrene Mission School in Zimbabwe, where he taught painting and sculpture. Sharing a studio with her husband, Paul Quail, she began her ecclesiastical work in earnest in the early 1980s. She has carved freestanding sculptures and relief panels in stone and wood for many churches throughout the British Isles and also for churches abroad. Among these commissions are reliefs for the fountain of the Roman Catholic Shrine at Walsingham and sculptures at St. Margaret Cley and St. Paul Goodmayes.

The Guild Chantry Chapel of St. Michael and the Holy Souls, designed by Laurence King in 1965, is the most modern of the worship spaces at the Anglican Shrine. The chapel has abstract glass, a crucifix carved in wood by Siegfried Pietsch, and a low-relief fiberglass sculpture by John Hayward depicting St. Michael defeating Satan. Both Pietsch and Hayward worked with the Faith Craft organization, which was based at one time in the Abbey Mill in the city of St. Albans. “For over 50 years Faith Craft artists and designers produced stained glass, vestments, statues and other carvings, liturgical furniture, sacred vessels and other ornaments for the beautification of God’s worship” (source).

+++

Hayward also designed and executed the east window at St. Mary and All Saints Little Walsingham. His complex design includes saints to which the church is dedicated, other sites of pilgrimage, founders of monastic orders associated with Walsingham, the story of Walsingham, and the fire that devastated this church in 1961. The window was installed for the re-consecration of the church in 1964.

Hayward is famous for his distinctive stained glass windows, such as the Great West Window in Sherborne Abbey, Dorset, and the Millennium Window at Norwich Cathedral. In the early 1960s, however, he was interested in creating “whole interiors” of churches, including not just stained glass but also wall paintings and furnishings. St. Michael’s London Fields is a good example of a church where Hayward had the opportunity to do this. His art is integral to the fabric of this basilica-style building and includes the Apostles’ Windows on the east side of the church, nine murals depicting scenes of the ministry of angels throughout the Bible, an aluminum sculpture of St. Michael slaying the dragon at the entrance of the church, and the Christus Rex hanging over the altar. Like Nugent F. Cachemaille-Day, Hayward drew inspiration from the liturgical movement, believing that art could be the “handmaid of liturgy.”

Following exhibitions at St. Mary’s and with the support of Art in Churches, three works of contemporary art were added to the church (all grouped at the entrance to the Lady Chapel) between 1985 and 1988. Spring Carpet is a painting by John Riches, who taught at the Norwich School of Art from 1972 to 1990. His interest in church iconography and medieval decoration strongly influenced his later work. Spring Carpet speaks of new life by means of light filtered through branches, speckling the earth. Genesis is a sculpture in resin bronze by Naomi Blake that is dedicated to the sanctity of life and depicts a mother and child. Blake is a Jewish sculptor, born in Czechoslovakia, whose work can also be seen at Bristol and Norwich Cathedrals. Ruth Duckworth’s untitled ceramic relief was installed at St. Mary’s in 1988 with the support of Art in Churches. The colored folds that emerge from the alcove in two distinct sections suggest, in one interpretation, this present life and the life to come.

A note from the director of art in churches says that these works have been carefully placed to distinguish them from liturgical artifacts also in the church. He wants them to be seen as “works of art” that enrich our beings beyond “the confines of the spiritual liturgical.” This note illustrates a strand of thinking that sees art and artists as independent yet complementary to the church, as opposed to the belief, within the liturgical movement, that art is the handmaid of the liturgy. Both perspectives have value while also raising issues for debate and discussion. Justine Grace, in The Spirit of Collaboration, writes of church commissions being perceived in modernism as being “ruled by the dogmatic prescriptions of the church rather than the artistic imagination.” At the same time, the example of Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce du Plateau d’Assy, for which contemporary masters were explicitly commissioned by Pére Marie-Alain Couturier, demonstrates, in some instances, artists unfamiliar with the liturgy translating the subjects chosen into “purely personal philosophies” (William S. Rubin, Modern Sacred Art and the Church of Assy [Columbia University Press, 1961]).

+++

The Roman Catholic Church of the Annunciation is a beautiful new church in the Norfolk round-tower tradition. Designed by local architect and parishioner Anthony Rossi, it is the first carbon-neutral church in the UK being built with solar panels for electricity and a deep borehole heat exchanger system. Located in the heart of historic Walsingham, it was dedicated on the Feast of the Annunciation in 2007. This “new church has taken traditional forms and materials and repackaged them in a fresh and innovative way to create a locally distinctive building” (source).

The architecture and artworks in this church illustrate what can be achieved when using artists who are either involved with the “alternative” world of church decoration or who are not generally reckoned to be contemporary “masters.” “The west and east windows have simple patterns of leads of varying widths, with accents of colour produced by handmade glass. They were designed by the architect and made by M C Lead Glaziers from near Norwich. The same firm fitted the dominant north window designed and made by the artist Paul San Casciani of Oxford. Hung against it is a powerful bronze corpus of the dead Christ by the artist Mark Coreth from near Salisbury. Other decorative glass in the aumbry, font and entrance screen is by Jane Charles of Newcastle, supplied through the Bircham Gallery at Holt.”

“Best known for his wonderful portrayal of the wildlife of Africa, Mark Coreth has that rare ability to capture the unique wild spirit of a creature without descending to kitsch. He is self-taught, relying on his very perceptive eye and instinctive understanding of animals.” Jane Charles is one of the leading contemporary glassmakers in the UK. Her inspiration comes from working with molten glass together with the shapes, colors, and moods of the natural world. Paul San Casciani is a specialist glass painter who has worked on commissions for notable buildings such as Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral and who likes to explore the decorative possibilities of stained glass, combining traditional and modern techniques in novel ways. While at the Whitefriars Studio, he worked with Ervin Bossanyi. His book, The Technique of Decorative Stained Glass, is a project-based guide and reference that explains traditional and modern techniques of stained glass.

According to the Parish Guide, “The combination of the powerful sculpture of the dead Christ and the light radiating from the centre of the window is designed to represent Christ’s crucifixion followed by his Resurrection, and the redemption and transfiguration of the human race through Christ’s sacrifice on Calvary. The design is based on the early Christian sign of the fish. The hill of Calvary is represented by the green tones at the base of the window and the red areas, with enlarged blood corpuscles, represent Christ’s Precious Blood. The deep blue glass suggests the darkened sky of Good Friday being dispersed by the radiating light of the Resurrection.

“The sculptor wished to show Christ at the point of death, and the wound in His side, which followed His death, is therefore omitted. The figure was initially modeled in clay and subsequently cast in bronze, and was exhibited in London with other sculptures by the same artist before being brought to Walsingham and installed in the church.”

+++

Finally, “the inspiration for establishing an Orthodox church presence in Walsingham began with the building of the Anglican Shrine in 1931. Inspired by one of the Guardians of the Shrine, Fr Hope Patten invited the Orthodox to take part in the venture. Archbishop Seraphim of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile in Paris came to bless a plot of land to the south of the restored Holy House, with the intention of building an Orthodox chapel.

“Though this plan was never carried out, a small Orthodox chapel was included in the Shrine, furnished with an icon screen and all the features necessary for Orthodox worship. In 1966 the Administrator of the Shrine asked the Orthodox to take responsibility for the care of the chapel. A missionary Brotherhood of St Seraphim was formed to establish a permanent presence in Walsingham. Its task was to include iconography, printing English texts of Orthodox services, missionary activity, and work with the poor and homeless. From here, the Orthodox presence really took off” (source).

“St. Seraphim’s story really begins in 1966 when Fr. Mark (later to become Fr. David) and Leon Liddament came to Walsingham as part of the newly formed Brotherhood of St. Seraphim. Their role at the time was to look after the little Orthodox Chapel that had been built in the Anglican Shrine; however, they soon felt that the local Orthodox needed a larger church. Looking around, the only buildings that were available at the time were the old prison and the old railway station. Finding the station a better option, they set about converting the building to its current form, which, as the building was being rented from the council, left it practically the same as the railway days with the addition of an onion dome and cross. While in the beginning they had planned to live and work in the rooms adjoining the chapel, events led to the establishment of a monastery in Dunton and a parish church in Great Walsingham, the Church of the Holy Transfiguration. However, St. Seraphim’s has remained a pilgrim chapel open to all who visit Walsingham since its establishment. St. Seraphim’s Trust was formed in 2005 and the building was finally purchased in 2008. Throughout its history, St. Seraphim’s has been a centre for the creation of Orthodox Icons with both Leon and Fr. David earning their livings as full time iconographers. While both have sadly passed away, Fr. David in 1993 and Leon in 2010, the Trust aims to build on their legacy and make St. Seraphim’s a space for the study and practice of iconography once again, reflecting the life and work of St. Seraphim of Sarov through publications, literature and icons.

“The next part of the project will involve informing people about the role of icons in Orthodox worship, private prayer and the traditional methods for their creation. As an important part of Walsingham’s history, the station platform will be restored and the Chapel garden is being developed as a community garden. This will be a natural space to complement the spirituality of the Chapel and provide a calming and natural reflective space for use by pilgrims and the whole community locally.

“Both iconographers used traditional methods of egg tempera painting and developed their own distinct styles. They drew their inspiration from both Greek and Russian sources, as well as Celtic ornamentation. This allowed them to develop an iconography which satisfied their own simple spirituality as well as those who bought their icons. The commitment of Leon Liddament and Father David to painting Icons of local and British Saints is of particular importance, and their Icons can be found all over the world as well as the British Isles” (source).

“The icon of our Lord in Glory, commissioned by St John the Divine Church, Kennington, London, is an example of a commission carried out by the Walsingham iconographers.”

According to Praying with Icons (St. Seraphim’s Trust/Norwich Cathedral, 2014), “The current icon screen (Iconostasis) in St Seraphim’s Chapel dates from 1975. On the right of the Royal Doors is the icon of Christ and on the left is the Mother of God. The Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John are on the Royal Doors, below the Annunciation. The screen separates the altar, where the priest serves, from the people in the chapel.

“At the top of the screen below the Cross is the last Supper. St Seraphim, Patron Saint of the Chapel, is on the right side of the screen and St Nicholas is on the left. In the centre of the ceiling under the dome is Christ Pantocrator, the Heavenly, looking down on he people. The icons of the Saints around the wall are venerated by the people.

“The blessing prayer for an icon is: ‘O Lord God, You created man in Your image, but the Fall darkened its brilliance. By the incarnation of Your Christ become Man, You restored the image and thus re-established Your Saints in their first dignity. In venerating Your Saints we venerate Your image and likeness. Through them, we glorify You as their archetype.’”

+++

The Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, www.walsinghamanglican.org.uk

St Mary & All Saints Little Walsingham, http://www.achurchnearyou.com/little-walsingham-st-mary-all-saints/

RC Parish Church of the Annunciation, http://www.catholiceastanglia.org/diocese/index.php?module=doea&group=56

St Seraphim’s Trust, www.iconpainter.org.uk

Photos: Beatitude Stations of the Cross (IV) by Jane Quail at the Anglican Shrine; interior of the Church of the Annunciation; interior of St. Seraphim’s Chapel.

Jonathan Evens is Associate Vicar, Partnership Development at St Martin-in-the-Fields, London, England. A keen blogger, he posts regularly on issues of faith and culture at http://joninbetween.blogspot.co.uk. His journalism and art criticism ranges from Pugin to U2 and has appeared in a range of publications, including Artlyst and Church Times. He runs a visual arts organisation called commission4mission, which encourages churches to commission contemporary art and, together with the artist Henry Shelton, has published two collections of meditations and images on Christ's Passion. Together with the musician Peter Banks, he has published a book on faith and music entitled ‘The Secret Chord’.