Antoni Gaudi

Antoni Gaudi

by Jonathan Evens

The great Australian art critic Robert Hughes viewed Gaudí's religious conservatism as ‘fused with the retention of Catalan identity’ so that, ‘when the church wanted a new counter-reformation based on an extreme ratcheting-up of cultic devotion to Jesus, Mary and the saints, Gaudí conceived his temple’ – the Sagrada Familia or (to give its full name) the Expiatory Temple of the Holy Family – as a means to that end, ‘an ecstatically repressive building that would help atone for the "excesses" of democracy.’1

|

|

While not denying that such ideas were part of the mix which led to the decision to create the Sagrada Familia and to appoint Gaudí as its eventual architect, I would defy anyone to enter the building itself and think that a dour, repressive penitence were its primary objective.

Gaudí is the great sculptor who utilises natural form in his work both for utilitarian and aesthetic reasons. He described nature as ‘the Great Book, always open, that we should force ourselves to read’ and, as Hughes recognised, thought that ‘everything structural or ornamental that an architect might imagine was already prefigured in natural form, in limestone grottoes or dry bones, in a beetle's shining wing case or the thrust of an ancient olive trunk.’

As a result first and overall impressions of his work are ones of exuberance and abundance characterised by the sinuous, sensuous curves and colours of his works. Whether we are encountering the shifting sea-like blues of the Casa Batlló, the abstract collage of the wave-like trencadis bench at Park Güell or the whirlpool-like undulations on the ceiling at Casa Milà, Gaudí's work possesses an ecstatic sense of natural beauty.

Similarly, the Sagrada Familia is primarily experienced as a forest of columns through which light falls in glowing colours. As in medieval cathedrals the eye is drawn upwards towards the light and glory of God, with the eye here drawn upwards by means of slender trunk-like columns, which branch (for reasons of form and function) before the ceiling of the basilica, where natural and artificial light mingle in star-like shapes resembling sunflower heads. Lower down the abstract stained glass of Joan Vila-Grau filters the blazing natural light of the Catalan sun through primary colours to create a sense of mystery even among the thousands of tourists crowding the space for the best camera angles.

Here, among the columnar forest and stained light (if one ignores the baldachin which is an example of the gaudy Gaudí), there is an almost total absence of explicit Christian iconography, creating a special interior sense of spiritual space. Unlike a medieval cathedral where the Christian story is told inside in stained glass, Gaudí placed the narrative element on the exterior of the building to form a Bible written in stone through three facades: Nativity, Passion and Glory.

The Nativity facade, although undertaken by other sculptors (primarily Llorenç Matamala), was Gaudí’s blueprint for how the facades were to look. The three porticos, symbolising hope, charity and faith, feature scenes from the birth, childhood and adolescence of Christ. Gaudí’s originality as an architect is found in natural forms utilised as abstract structure or decoration and this means that the somewhat stylised realism of these sculptures is far from being at the original or emotive heart of the Sagrada Familia project. However, the sheer abundance of carving and symbol on this facade does create the unique look of this building. ‘Columns and arches melt into a viscous jism that foams, drips and procreates foliage, beasts and people.’ As Rowan Moore has stated, ‘No other architect has made stone look so fluid, so dissolving.’2

Although driven, single and celibate, Gaudí was not a simple ascetic. He surrounded himself with a patron (Eusebi Güell) and work colleagues (Josep M. Jujol and Francesc Berenguer, among others) with whom he socialised and to whom he gave significant responsibility. He also knew that he and his team (‘one sole generation’) could not erect an ‘entire temple’. Therefore he planned for future generations to work on his temple using the ‘vigorous display of our passage’ as their encouragement and inspiration.

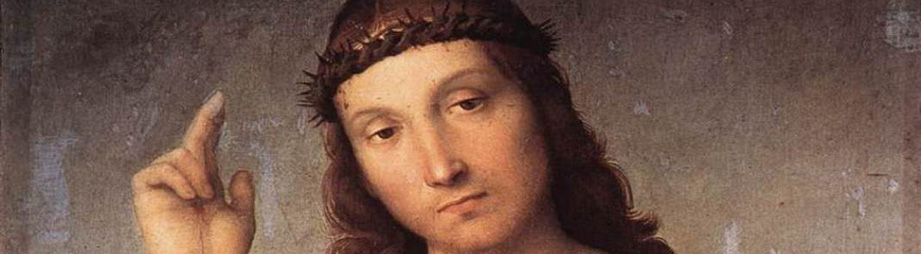

One such is Josep Maria Subirachs, a Catalan sculptor whose expressionistic work forms the doors and sculptures of the Passion facade. His angular style is a significant contrast to Gaudí’s flowing forms, yet is better suited to capturing the anguish and pain of Christ’s Passion in figures which, in the Crucifixion scene, echo the secular crucifixion of Picasso’s Guernica.

Gaudí and his primary patron, Eusebi Güell, were men of great vision and vast ambition resulting in several projects - Park Güell and the Crypt of Colònia Güell - which, although failures in terms of their original intent, are today rightly recognised as being among Gaudí’s primary masterpieces. Park Güell being a real estate venture where only two homes were built and the Crypt of Colònia Güell being only the lower nave of what was intended to be a larger building. Their example suggests that to reach for the impossible and fail can nevertheless result in significant achievement. Park Güell is now public space and a major tourist attraction while the Crypt of Colònia Güell is in the words of Robert Hughes through ‘its logic of construction, its sheer blazing inventiveness … one of the world's most sublime architectural spaces.'

The Crypt of Colònia Güell is a culminating point in Gaudi's work, where he included for the first time practically all of his architectural innovations. He stated that without the large-scale experiments he undertook there, he would not have dared apply those same geometries to the Sagrada Familia. It is the place where, according to Japanese architect, Arata Isozaki, he ‘overcame all established limits regarding shapes.’3

This church of Colònia Güell was blessed by the Bishop of Barcelona in 1915 and today functions both as parish church and tourist attraction. Like the Sagrada Familia, albeit on a smaller more intimate scale, its varied columns form a wood of trees. Flower-like cross shaped stained glass in primary colours creates a warmth to the space which is complemented by the red brick forming the walls and catenary arches of this cave-like space. A thin crucifix hangs over the altar, almost unseen and visually unnecessary, as both the columns and Gaudí’s ergonomically designed benches direct the eye to the sanctuary and its gleaming stone altar.

This is a warm, womb-like enclosure; intimate yet archetypal. It is real and usable communal space while also being of great architectural worth, innovation and beauty. Here the ‘heaven in ordinarie’ of the Eucharist is celebrated in the surround of natural forms recreated by man-made means.

It is said that Gaudí’s aim at the Sagrada Familia was to bring heaven and earth together. It may well be that this aim is more fully realised in the earthy intimacy of the Colònia Güell’s wooded Crypt than in the soaring grandeur of the Sagrada Familia.

*******

Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926) was a Catalan architect of Spanish nationality born in Reus or Riudoms in Catalonia, and figurehead of Catalan Modernism. Gaudí's works reflect his highly individual and distinctive style and are largely concentrated in the Catalan capital of Barcelona. Much of Gaudí's work was marked by his big passions in life: architecture, nature and his Catholic faith. Gaudí integrated into his architecture a series of crafts in which he was skilled: ceramics, stained glass, wrought ironwork and carpentry. He introduced new techniques in the treatment of materials, such as trencadis, made of waste ceramic pieces. After a few years under the influence of neo-Gothic art and Oriental techniques, Gaudí became part of the Modernista movement which was reaching its peak in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work transcended mainstream Modernism, culminating in an organic style inspired by nature. Gaudí rarely drew detailed plans of his works, instead preferring to create them as three-dimensional scale models and molding the details as he was conceiving them. Gaudí's work enjoys widespread international appeal and many studies are devoted to understanding his architecture. His masterpiece, the still-uncompleted Sagrada Família, is one of the most visited monuments in Catalonia. Between 1984 and 2005 seven of his works were declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO. Gaudí's Roman Catholic faith intensified during his life and religious images permeate his work. This earned him the nickname ‘God's Architect’.

Jonathan Evens is an Anglican priest who is secretary to commission4mission, which aims to encourage the commissioning and placing of contemporary art in churches as a means of fundraising for charities and as a mission opportunity for the churches involved. His journalism and creative writing has appeared in a range of periodicals. See http://commissionformission.blogspot.com for more information.

1. ‘Reach for the Skies’ by Robert Hughes, The Guardian, Saturday 10 February 2007 (www.theguardian.com/books/2007/feb/10/architecture.spain).

2. Sagrada Familia: Gaudí's cathedral is nearly done, but would he have liked it?’ by Rowan MooreThe Observer, Sunday 24 April 2011 (www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/apr/24/gaudi-sagrada-familia-rowan-moore).