France: Notre-Dame de Toute Grace, Assy

Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce (Our Lady of All Grace), Plateau d’Assy, France

by Jonathan Evens

Planned as a showcase for the value of modern church commissions, the Dominican-inspired church of Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce in Plateau d’Assy (or Assy), France, elicited diverse reactions of praise and condemnation when it was consecrated in August 1950. Many hoped it would set off a renaissance of sacred art in Europe, but others disapproved strongly of its commissioning of secular artists.

Marie-Alain Couturier—in collaboration with the parish priest at Assy, Canon Jean Devemy—had made this controversial decision to commission work from well-known artists working outside the church, including Pierre Bonnard, Marc Chagall, Ferdinand Léger, Jacques Lipchitz, Jean Lurçat, and Henri Matisse. A Dominican friar and editor of the journal L’art sacré, Couturier claimed along with coeditor Pie-Raymond Régamey that “each generation must appeal to the masters of living art, and today those masters come first from secular art.”

This meant, as art historian William S. Rubin writes in his book Modern Sacred Art and the Church of Assy, that “side by side with works of the pious Catholic Rouault one saw those of Jews, atheists, and even Communists – a revolutionary situation that struck the keynote of a new evangelical spirit.” As a result, “even before its dedication in 1950, the church had become the center of an increasingly bitter dispute which was to cause a marked rupture between the liberal and conservative wings of the clergy and laity during the following years. The violent polemics on both sides involved not only the French Church, but also the Vatican, usually through the voice of the Congregation of the Holy Office. As its destiny was linked to the fortunes of the entire liberal religious movement in France, the Church at Assy and its decorations were vehemently attacked and defended by an army of critics, most of whom had seen only a few photographs of the works in question.”

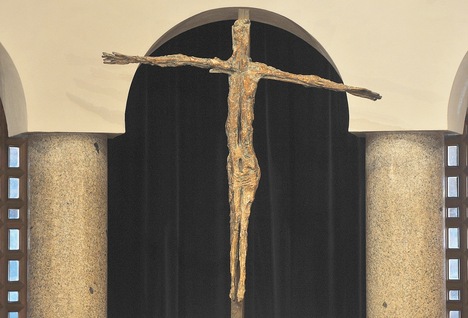

The polemic against the Assy commissions was centered on the bronze crucifix created by Germaine Richier, but this quickly turned into a wide-ranging attack by traditionalists on the desire of French Dominicans for a Christianity that engaged with the secular world. The French Dominicans argued that priests should not live apart from the world but should join with the citizenry “to establish a new, spiritually inspired system of social justice”—the worker-priest movement—and, with artists, preach a “new gospel of sacred art” that could help these artists come to “Christian awareness.” These initiatives were representative of a new concern for contextualized mission.

Featuring an undefined figure in a cruciform shape, Richier’s crucifix resembles “craggy and weathered wood” and therefore has a “tortured and sacrificial appearance.” It is a stunning image of the effect suffering has on human beings by reducing one to mere flesh and bone. Couturier related the image to the “root out of dry ground” of Isaiah 53.

Richier’s crucifix connects with the strand in modern sacred art, exemplified by Albert Servaes and Graham Sutherland, that views Christ’s sacrifice as emblematic of human suffering in conflict and persecution. Works in this vein were often controversial, as they challenged sentimental images of Christ and deliberately introduced ugliness into beautiful buildings. Richier’s crucifix was described by those who opposed its inclusion in the church as a caricature of a crucifix in which it was no longer possible to “recognise the adorable humanity of Christ,” making it “an insult to the majesty of God” and “a scandal for the piety of the faithful.”

Servaes and Richier were both affected by decrees from the Holy Office and saw their artworks removed from the churches for which they had been commissioned. The instruction on sacred art issued by the Holy Office in 1952 was the beginning of a two-year initiative by the Vatican that severely constrained the modernizing program of the French Dominicans and represented a victory for the traditionalists within the Church.

Richier’s crucifix has, though, subsequently been returned to its place in the sanctuary at Assy, and the church, like many other art sacré churches, is classed by the French government as a national monument—the secular state recognizing the value of sacred art commissions—and has become a significant tourist location. As a similar level of acceptance and understanding has also evolved in relation to other controversial commissions, including those by Servaes and Sutherland, it would seem that scandals of modern church commissions are, with time, resolved as congregations and communities live with the works and learn to value the challenge of what initially seemed scandalous.

The architect of Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce was Maurice Novarina, whom Jean Devemy selected on the basis of his work at Notre-Dame des Alpes (Our Lady of the Alps) in Le Fayet. Novarina used his regional style at Assy with a chalet-style pitched roof and locally sourced materials. The chalet style is intimate and warm, while the wooden carved beams suggest a Nordic hall. The interior is dark as a result, but this tends to set off the artwork well.

.jpg)

Couturier was in charge of the art commissions. As most of these were given on the basis of his friendships with the artists involved, the decisions he made or did not make illustrate the tricky balance required to succeed in commissioning. Couturier criticized the Ateliers d’Art Sacré (Studios of Sacred Art) of his day for being a “world closed in on itself, where reciprocal indulgence, or else mutual admiration, quickly becomes the ransom paid to work as a team and maintain friendship.” Yet Couturier’s scheme of work at Assy suffers from the opposite problem, as work by individual masters produced in isolation from each other, assigned on the basis of what they could with integrity contribute, results in a decorative scheme with no cohesiveness or focus. As Rubin states, “the subject was almost as often picked for the man as the man for the subject.”

Too much work was commissioned for the church at Assy from too many artists, and because Couturier failed to exercise sufficient control over the overall iconographic scheme, that scheme is muddled. There are inappropriate clashes of style (e.g., the Lipchitz sculpture dominating the Rouault windows, and the different styles used in each of the nave windows), an inappropriate positioning of some works (e.g., stained glass by Bazaine and reliefs by Chagall that can barely be seen), commissions that do not work in the space (e.g., the intimate style of Bonnard is not suited to being viewed from a distance), and central commissions with esoteric symbolism (e.g., the Lurçat tapestry). At Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce, the whole is not greater than the sum of its parts.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

|

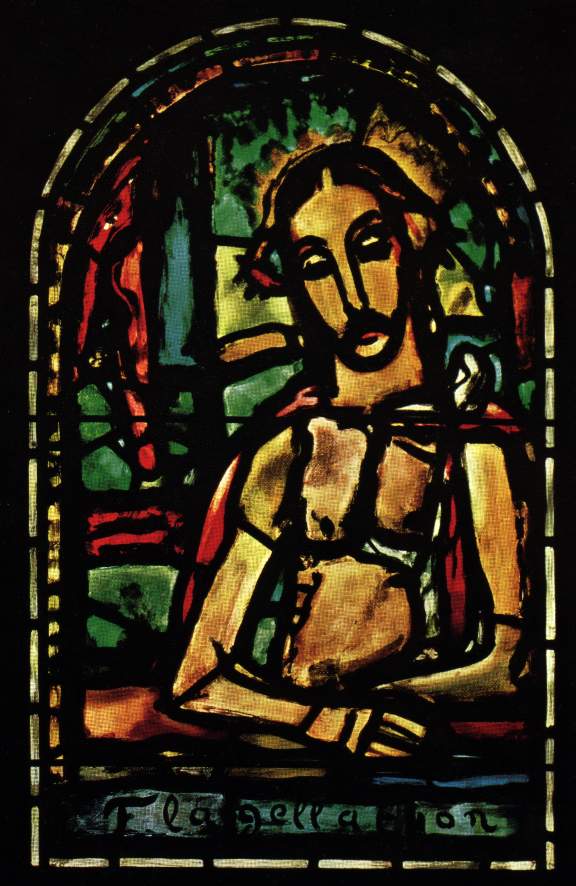

The overall lesson of Assy would seem to be that simplicity is of the essence. The most effective works are those that are simplest, clearest, and most pared back, such as the work by Léger, Matisse, Richier, and Georges Rouault. The Rouault windows in particular are luminous combinations of beauty and sorrow, effective translations of the artist’s paintings into stained glass. The floral windows seem a strange choice initially but function as memento mori, a reminder of man’s mortality.

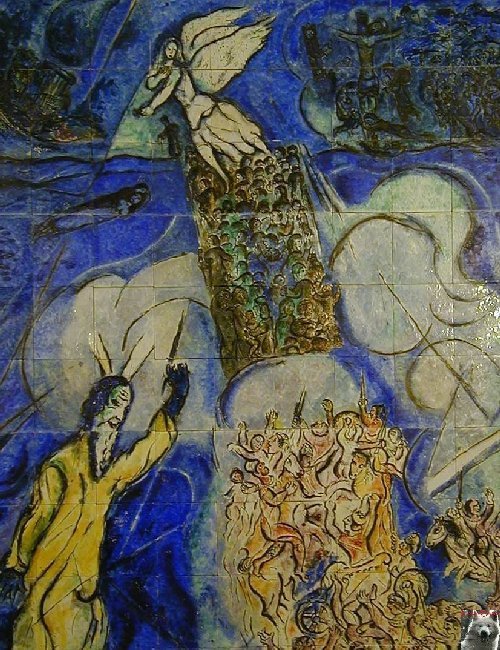

The Jewish artist Marc Chagall created for the church a wonderful Exodus mural on ceramic tiles, which is hung in the baptistery. The subject matter is an inspired choice for that location, because for Christians the crossing from bondage to freedom via the Red Sea harks forward to the sacrament of baptism. Although Chagall was uncertain about undertaking this first commission for a church, his work here shows clearly the suitability of his vision and practice for churches and led to many subsequent church commissions.

The Lurçat tapestry, by contrast, is ineffective both in itself and as a central focus. Its imagery is undeniably personal and esoteric. It provides visual focus through its size but, although intended as an apocalyptic evocation of the conflict between good and evil, fails to convey menace or threat. The beast looks funny and friendly, suitable for a walk-on part in Teletubbies or In the Night Garden, and the female figure that opposes it is a nonentity. The work of Adam Kossowski at St. Benet’s Church, Mile End, England and St. Mary’s Church, Leyland, England provides much stronger examples of apocalyptic imagery put to devotional use. That said, Lurçat’s work is by no means fundamentally unsuited to an ecclesiastical context, as his vibrant Creation tapestry for the Chapel at the Bishop Otter Campus of the University of Chichester, England, ably demonstrates.

As noted earlier, Couturier and Régamey argued that “each generation must appeal to the masters of living art, and today those masters come first from secular art.” However, fashions and reputations in the art world (as elsewhere) change considerably with time. In their own day and time Picasso and Matisse were considered unassailable as the giants of twentieth-century art, while now, in terms of continuing influence on contemporary artists, Marcel Duchamp is generally considered the most influential twentieth-century artist. Lurçat’s tapestry provides the central focus for the church at Assy, where those artists commissioned were considered current masters, but his reputation has not been sustained into the present day, and the same is also true of Lipchitz.

The reputations of many of those who were commissioned by the Church in the twentieth century (Bazaine, Denis, Gleizes, Lurçat, Manessier, Sutherland, Piper, Rouault, Severini) have declined following their deaths. The same is likely to be so for those receiving contemporary commissions (i.e., Clarke, Cox, Emin, Le Brun, Wisniewski). The pace with which modern art moved from one movement to the next in the twentieth century quickly, and often unfairly, condemned as passé what had previously been avant-garde.

The Church cannot, and probably should not, seek to keep up with the fickle nature of fashion and instead should value both those artists with significant mainstream reputations wishing to receive occasional commissions and artists with less significant mainstream reputations for whom commissions form a significant part of their practice. That combination is what we find at Assy.

However, it’s unhelpful to set up a dichotomy between artists with significant mainstream reputations and those without, and between secular artists and artists who are Christians. The reality is that modern and contemporary church commissions have been given to both groups of artists simultaneously, and both have resulted in successes and failures. What is warranted and rewarded is sustained and prayerful attention to each and every artwork in order to discern what is good and of God in and through it.

*******

Jonathan Evens is Priest-in-Charge at St Stephen Walbrook and Associate Vicar for Partnership Development at St Martin-in-the-Fields, London, England. A keen blogger, he posts regularly on issues of faith and culture at http://joninbetween.blogspot.co.uk. His journalism and art criticism ranges from A.W.N. Pugin to U2 and has appeared in a range of publications, including Art & Christianity and the Church Times. He runs a visual arts organisation called commission4mission (c4m), which encourages churches to commission contemporary art and, together with the artist Henry Shelton, has published two collections of meditations and images on Christ's Passion. Together with the musician Peter Banks, he has recently published a book on faith and music entitled The Secret Chord.