Moses and his Nubian Wife - Jacob Jordaens

Jacob Jordaens: Moses and his Nubian Wife

.jpg)

A Lesson in Love

by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker

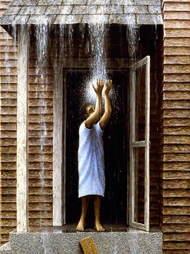

The title gives it away. In this painting Moses is depicted with his Nubian or Ethiopian wife. We can recognize him by the table of the law in his left hand. The woman is richly dressed and wears an extravagant African sun hat. With her right hand she points to her heart. The woman looks away, Moses is looking us in the eye. He makes a questioning gesture with his right hand. Vulnerably they ask us a question. What do you think of us? Do you reject us as well?

The Flemish Baroque painter Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678) is not the only one who has painted this subject, but the way he has portrayed it, is unique. He has not set out to tell us the story in Numbers 12 about Moses and his wife, rather he wants to make us think, present us with a lesson, as did so much of 16th and 17th-century art of the Southern and Northern Netherlands.

Were black people portrayed often in Western art? And how did people think about Africans at this time? Only in the 15th century did European artists start to depict black people in such biblical themes as the Adoration of the Magi and the Baptism of the Ethiopian Eunuch. Both these themes stress that salvation is for all the peoples of the earth. In the medieval church black people were considered the descendants of Ham (the son of Noah who shamed his father as described in Genesis 9) and approached less positively. How they were viewed in the 17th century at the time of the slave trade is not hard to guess. Jordaens definitely had his reasons for making this radical antiracist work. Having converted to Calvinism in a Catholic environment he may have been extra aware of the impact of discrimination.

Probably you are not the only one, when you did not know that Moses had a Nubian wife. It is a detail that is readily missed. Moses, however, also had another wife called Zipporah, daughter of Jethro, who was a priest in Midian (see Exodus 2:21). Various theories about these two wives of Moses can be found. Most plausible to me seems the explanation that during the reign of Tuthmose III Moses as Egyptian crown prince and general put down a Nubian revolt and married a Nubian princess. When, around 20 years later, he abruptly had to flee from Egypt, he probably left her behind. In Midian he marries anew, as he must have considered his life in Egypt a closed chapter.

Forty years later, upon his return in Egypt, Moses probably reunited with his first wife (on his way to Egypt he sent back Zipporah and his sons to her father Jethro). The Ethiopian must have gone with Moses when the Israelites set out on the exodus. When they have arrived atMountHoreb, Jethro then brings Zipporah and his sons back to Moses. Which means that during the events in Numbers 12 Moses must have had two wives. This was, however, tacitly permitted during this time. Marriages with women from a number of idol worshipping peoples were forbidden, unless they had adopted the Jewish faith.

Jordaens definitely had his reasons for making this radical antiracist work.

‘Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses because of the Cushite [Ethiopian] woman whom he had married.’ They continued their assault on Moses with the assertion: ‘Has the Lord spoken only through Moses? Has he not spoken through us also?’ It looks like we have ended up in a common power struggle. You can already see the very humble Moses – ‘more so than anyone else on the face of the earth,’ says the text – step down from his position, but God quickly reinstates him. ‘Suddenly’ he orders the three to come to the tent of meeting. There he makes clear that as a prophet Moses belongs to a class of his own. With Moses he speaks face to face, but to Miriam and Aaron in dreams and visions. ‘Why then were you not afraid to speak against my servant Moses?’ And the anger of the Lord was kindled against them and Miriam becomes leprous. White as snow she became, as she was unwilling to accept her black sister-in-law.

God steps into the breach for the black woman and her marriage to Moses. How wonderful! God puts the spirit of the law above the letter of the law, just like Jesus does later. The law is meant to protect those who are vulnerable and to show what love and real life is. This is exactly what also Jesus wants to give to us: real life, life with God, life with love. Is that why the hat of the woman has the form of a cruciform halo, which is normally reserved for Jesus ? Possibly Jordaens reaches back to an old tradition here, which sees Moses as an image for Christ and his wife as an image for the Church (the body of Christ), by portraying Moses’ despised black wife in this capacity. In any case Jordaens stresses with this special halo that we should regard this black woman in Christ, who teaches us to love our neighbour as ourselves.

*******

Jacob Jordaens: Moses and his Nubian Wife, 1650, oil on canvas, 106,5 x 80 cm, Rubens House, Antwerp.

Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678) was a Flemish Baroque painter. From the time of Peter Paul Rubens' death in 1640, Jacob Jordaens was in greater demand than any other artist in northern Europe. He remained Antwerp's leading figure painter until his death. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Jordaens never went to Italy. He was born and lived his whole life in Antwerp, where he and his friend Rubens shared the same teacher, Adam Van Noort. In the 1620s Jordaens built a flourishing studio while also frequently assisting Rubens. His style is based on Rubens' exuberance, but with a stronger contrast of light and dark as well as a thicker layering of paint. Despite converting from Catholicism to Calvinism in mid-life, Jordaens received numerous commissions for Catholic churches. A masterful technician, Jordaens' prolific output includes altarpieces, portraits, genre, and mythological scenes. He also produced watercolours, tapestry designs and engravings. His late works include large genre scenes.

Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker is Editor-in-Chief of ArtWay.

ArtWay Visual Meditation February 23, 2014