England: Church of St Pauls, Goodmayes, Essex

Church of St. Paul’s, Goodmayes, Essex

by Jonathan Evens

St. Paul’s Church in the Goodmayes district of northeast London was built in response to the development of the Mayfield Estate, a neighbourhood of good-quality but affordable houses geared toward clerks and lower-grade civil servants. Building began in 1901 and was completed in 1917 by Messrs. Brown & Son of Braintree, following Gothic-style designs by the architectural firm Messrs. Chancellor & Son of Chelmsford and London. The church was consecrated by the Lord Bishop of Chelmsford, the Right Reverend John Edwin on March 22, 1917, at which point St. Paul’s became the independent parish church of Goodmayes.

Ever since its founding, St. Paul’s Goodmayes has been a prolific and generous patron of the arts. It contains a vast array of artwork reflecting the movement in church art from the medievalism of the Arts and Crafts movement through the angular, Cubist influences of Leonard Evetts to the semiabstract work of contemporary artist Henry Shelton, as well as a range of materials, including stained glass, silver, brass, copper, stone, wood, oil, watercolors, wrought iron, gilding, and ceramics. Contributing studios include Fullers, Morris & Co., Whitefriars, and the Faith Craft Company, with designs from artists such as Sir Edward Burne-Jones, J. H. Dearle, Leonard Evetts, Alfred Fisher, Jane Quail, and Henry Shelton.

The church’s website documents its many commissions, revealing the value of memorial bequests for the commissioning of church art.

East Window of the Lady Chapel (Fullers Studio / Whitefriars Studio)

The first stained glass window to be commissioned for St. Paul’s was the East Window of the Lady Chapel, made by the Fullers Studio (by which the work of Geoffrey Fuller Webb may be indicated). In July 1944 this window was severely damaged by a bomb, leaving only the tracery (small upper windows) intact. These show the Arms of Canterbury and Chelmsford, flanked by St. Paul, the patron of the church, and St. Cedd, the seventh-century missionary-bishop of Essex.

The original main lights of the window showed Mary and the infant Christ, flanked by the wise men and the shepherds. The replacement, from 1957, is an entirely new design depicting the same scene, made by the Whitefriars Studio, a British glasshouse closely associated with leading architects and designers from the late nineteenth century onward, including Philip Webb. The window contains the studio’s mark, a White Friar, in the bottom right corner, and the artist has signed it with the trilby he wore in his workshop.

Morris & Co. Windows

Morris & Co. dominated British stained glass production during the 1870s and 1880s and is responsible for four of the windows inside St. Paul’s.

Main East Window

The East Window (pictured above) was donated by Leonard Randall, a generous benefactor of St. Paul’s. Dedicated on September 15, 1929, it shows Christ flanked by Martha and the three Marys: his mother, Mary of Bethany, and Mary Magdalene. The design is by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, the chief stained glass designer of his day. (A separate area at Merton Abbey, where Morris’s workshops were located from 1881 onward, was allocated to Burne-Jones’s glass workshops.)

Like the Lady Chapel window, the East Window received serious bomb damage in July 1944: according to the insurance valuation, only one-seventh of the original remained. Morris & Co. had to recreate and reinstall it in 1954.

St. Alban & St. George Window and St. Peter and St. Paul Window

The St. Alban and St. George window was donated by Leonard Randall in 1929 in memory of his nephew, who was killed in World War I. Located at the west end of the church, it features a contemporary design by J. H. Dearle, who also designed the figure of St. Peter for another west end window, installed in 1933, which was complemented by a figure of St. Paul to a design by Burne-Jones.

Main West Window

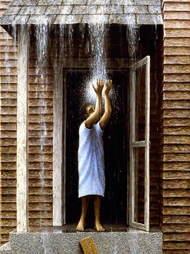

Between these two smaller windows is the main West Window, made, again, from a design by Burne-Jones. It was dedicated on December 18, 1932. Leonard Randall, the donor of several earlier windows, died in 1932, leaving a large sum to St. Paul’s, including £400 for a window in the new baptistery, which had been built into the west end of the church in 1929. The window depicts women bringing their children to Jesus so that he can bless them—a well-known Gospel scene. The inscription at the bottom is from Luke 18:16, which reads, “Suffer little children to come unto Me.”

David & Jonathan Window

The last of the Morris & Co. windows in St. Paul’s depicts David and Jonathan, and it was designed (in a rather different style from the others) by D. W. Dearle (not J. H.). This window cost £96.15s. in memory of Mr. A. E. Godfrey and was dedicated on September 4, 1949. Today it is the odd man out in the Lady Chapel, as the three surrounding windows all feature Our Lady and the events of Christ’s birth. In 1949, however, it was the only stained glass in the chapel (apart from the tracery over the East Window), the rest being added later.

Jesus the Carpenter Window (Faith Craft Company)

In 1963 the Jesus the Carpenter Window was made and installed by the Faith Craft Company. The Faith Craft Company was a studio set up through the Society of the Faith, which grew from vestment manufacture to encompass various aspects of church furniture, such as joinery, stained glass, and statuary. It was in operation from 1921 to 1972.

The center section of the window shows Jesus as an adult in his carpenter’s shop in Nazareth, surrounded by the tools of his trade. On the left is a roundel depicting a sower—the subject of one of Jesus’s parables—and on the right is St. Paul working as a tentmaker.

This unusual combination of images commemorates the longest-serving churchwarden of St. Paul’s, Foster Threadgold, who died in 1959, in his twenty-ninth year of office. Over one hundred people contributed financially to this memorial window, which is located on the north side of the church, as near as possible to the churchwarden’s seat.

The Evetts Windows

The prolific stained glass artist Leonard Evetts created the most recent windows at St. Paul’s—from 1975 and 1980.

Annunciation Window

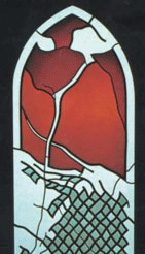

On June 1, 1973, parishioner Walter Tolbart died, leaving a substantial bequest to the church. He had expressed a wish that part of this money should be used for a window, and approaches were made to various artists, as a result, in 1974. Finally, in April 1975, the Parochial Church Council approved a design by Leonard Evetts depicting the Annunciation. The window was dedicated in memory of both Doreen and Walter Tolbart on November 30 of that year.

In the left light, the archangel Gabriel is drawn “to give the impression that on wing he has silently entered the drama, barely touching the earth,” to quote the artist’s description. The Virgin Mary is depicted on the right wearing the traditional blue robe, which is decorated with a lily. Gabriel’s salutation is written across the center in Latin: “Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum” (Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee). The Holy Spirit, by whose power Mary was to conceive, appears as a dove in the tracery, from whence descend shafts of light.

Visitation Window

Immediately after the Annunciation, Mary spent three months at the home of her cousin Elizabeth, soon-to-be mother of John the Baptist, and the two women rejoiced together over the sons they were to bear; Mary’s words of celebration included the Magnificat. This episode, traditionally referred to as the “Visitation,” is illustrated in a complementary window created in memory of Norah Sherren, dedicated on October 26, 1980. Sherren was among the most senior members of the church, having had been present at the laying of the foundation stone of St. Paul’s, and when she died at age 82, she left a considerable sum to the church, including £1,000 for a memorial window.

The Visitation took place in the hill country of Judea, which is represented in the window by the rocky scenery in the background. Elizabeth is shown on the left, Mary on the right—notice the blue robe and lilies once again. As with the Annunciation Window, Evetts’s signature is just visible: “L. C. Evetts fecit. 1980.” This was the last stained glass window to be installed in St. Paul’s to date.

St. Timothy Window (Whitefriars Studio)

Finally, the St. Timothy Window comes from the Whitefriars Studio and the hand of Alfred Fisher. Its bright, vivid colors were achieved by the use of handmade “Norman slab” glass, which retains its luster even in dull conditions. The window shows Timothy as a youthful figure, staff in hand, presumably engaged on some missionary journey.

In the two small tracery lights above are symbols of the activities for which Frank Hills, in whose memory the window was given, is remembered: he was a member of the choir for some forty years, which explains the page of music and the words “O sing unto the Lord,” and he was the warden at St. Paul’s for a time and was also involved in the Scout Movement, hence the churchwarden’s staff and the scout emblem. The words “Honour thy God” have a double significance: as well as representing a maxim by which Hills lived, they are also a play on the name Timothy, which is derived from two Greek words meaning “honor” and “God.”

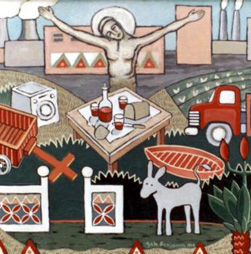

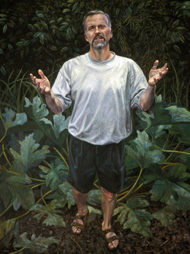

Madonna and Child and Stations of the Crown of Thorns

Father Benjamin Rutt-Field oversaw the addition to St. Paul’s Goodmayes of a Madonna and Child by the contemporary Roman Catholic sculptor Jane Quail and Henry Shelton’s Stations of the Crown of Thorns. It was his belief that “for Christian art to have any significance and empathy it must be Spirit-driven, Spirit-imprinted; it should stimulate both our imaginations and our prayers.”

The seed for the Shelton commission was sown by an elderly parishioner who gifted a generous sum for a new set of stations. It was carried out through commission4mission, an organization of which Shelton is a founding member and the current chairman. Shelton says of commission4mission, “I want us to be offering quality work and craftsmanship, rather than mass-produced work, to continue the legacy of the Church as a great commissioner of art. The Church has, in fact, commissioned some of the greatest works of art ever produced.”

There are fifteen paintings in all in Shelton’s series, as the scheme includes a resurrection station depicting Christ present in the Eucharistic elements. The central focus of the scheme is stations 11, 12, and 13, which form the altarpiece of the church. This triptych inventively incorporates an existing metal crucifix into its design to form station 12, “Jesus dies on the cross.”

By way of semiabstract imagery, Christ is depicted throughout only by the crown of thorns. Fr. Rutt-Field notes that “these stations are known as ‘the Crown of Thorns’ rather than ‘the Cross’ because Jesus is depicted in each one as a simple, humble crown of thorns.”

“As I’ve got older I’ve learnt that ‘less is more,’” Shelton says of his minimalistic style, “and through the development of my work I’ve learnt to express emotion in a semiabstract form.” This is why he paints: “it all goes back to feeling; the pathos of suffering.”

The power of art to evoke emotion is what originally inspired Shelton and what has sustained his work throughout his career: “When I first saw the great Rembrandts in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the power of his images seemed to transcend time. The same thing attracted me to Christian art as a choirboy at All Saints West Ham: the art spoke to me. I used to look at the altar and see images that were just so powerful. The images seemed to bring the past into the present and to form a profound link with the lineage of the past. I see myself as an artist trying in my small way to continue that lineage, and my passion as a Christian artist is to keep that lineage alive in my generation as a witness.”

However, as an artist who often paints with the tones and harmonies of the Dutch masters, Shelton had to considerably lighten his palette for the stations in order to harmonize their color scheme with the existing stained glass.

To have his art in churches, Shelton says, “really is the fulfillment of my life’s work.” He doesn’t have much ambition to show in galleries and says that “the whole point for me is to create reaction and engage people—for people to enjoy and be moved by my work, just as I’ve been engaged by the work of other artists.”

Shelton’s most recent images have come to him in prayer as he meditates on particular Bible passages. It is perhaps this meditational quality of Shelton’s work to which Fr. Rutt-Field is responding when he says, “I firmly believe that these new Stations of the Crown of Thorns, painted by a deeply committed Christian artist, are indeed both Spirit-driven and Spirit imprinted. They will greatly enhance and beautify the simple form and architectural lines of our parish church, as well as our worship.”

*******

As St. Paul’s Goodmayes is a neighboring parish to my own, I have had the opportunity to undertake ministry in partnership with Fr. Rutt-Field and his congregation, who make significant use of art even beyond those works on permanent display inside their own church. Art competitions and workshops have led to exhibitions timed to feature as part of community festivals, and a cluster of four local Anglican churches has created an Art Trail with a route that highlights artworks of interest in each of the churches. The creation of the Art Trail was a recommendation in the report produced following a Community Street Audit of Aldborough Road South by the Seven Kings and Newbury Park Residents Association and the Fitter for Walking project of Living Streets. Art Trail leaflets, printed with funding from Living Streets, can be found in the four churches.

Churches have for many years been significant patrons of the visual arts and contain many such treasures. The local Anglican churches in Aldborough Hatch, Goodmayes, and Seven Kings are no exception, with works of art by some of the best local and national artists of the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. The significant works of art in these churches, taken collectively, represent a major contribution to the legacy of the church as an important commissioner of art.

The rich and diverse range of work found at St. Paul’s Goodmayes demonstrates the ways in which the visual arts enhance worship and mission. The story of their commissions reveals the significance of memorial donations and the journey that church commissions made in the twentieth century from the medievalism of the Arts and Crafts movement to the semiabstract styles of contemporary artists.

.JPG)