Articles

.jpg)

.jpg)

Mikhail Vrubel

Mikhail Vrubel

.jpg)

.jpg)

Orthodox Church Painting - A. Mgaloblishvili

The Development of Church Painting in Countries of the Orthodox World (Greece, Russia, and Georgia) in the Early 20th Century

by Anna Mgaloblishvili

One significant aspect of the age-long history of Orthodox culture has been the quest for a universal art language in order to ensure mutual understanding and reciprocal enrichment among nations of different origins. The characteristics of Georgian church painting of the 20th century cannot be understood without taking into account the general processes in this field in various Orthodox countries. We will compare Georgian materials with the characteristics of church painting in the two greatest Orthodox countries - Greece and Russia - with which Georgia has had long-standing political and cultural links.

Greece

With the downfall of Constantinople in 1453, the greatest center of Orthodoxy and of the Byzantine Empire, begins the gradual decline of Eastern Christendom that is reflected in developments in Orthodox Christian art. While Greece was under Turkish rule from 1453 to 1830, the Christian faith and the desire to return to its former ‘Byzantine’ glory bеÑamе аn important driving fогÑе in the struggle for the ‘Great Idea’. Filled with the spirit of this idea national uprisings brought independence and freedom for the country in 1830.

Throughout the 16th and17th centuries Greek traditional art flowered, but bу the end of the 18th century the methods and peculiarities of the traditional Greek religious style were forgotten. At the same time on the Ionian Islands, which were fгее from Turkish rule, the bourgeois class progressively developed a taste fоr the western painting. In 1837 а school of fine art was founded in Athens. The best students of the school were sent to Europe fоr higher education, as а rule to the academy in Munich. Consequently Greek art was strongly influenced by the German academy. Оvеr а long period under the domination of Turkey the Greek church had endured tremendous oppression, but despite enormous difficulties had retained its original characteristics and traditions. Succeeding decades after the announcement of the country’s independence also turned out ambiguous in the history of Greek Church.

In 1833, in the name of Bavarian King Othon, the Greek Church was pronounced autocephalous by the Viceregency and was separated from the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople to which it had been subordinated for centuries. Ignoring the canonical law and age-long tradition of the Orthodox Church, the church was deprived autonomy, the patriarchal institute was abolished and the state took control of the church. Such changes provoked dissatisfaction both inside the country and abroad: the world patriarch refused to accept the Greek autocephalous church and it was left in full isolation from the rest of the Orthodox world (except Russia). In 1850 the Greek government was forced to recognize the autonomy of the church again.

The developments in the church promoted a revival of interest in matters of church painting. In the 50’s and 60’s of the 19th century the foundations were laid of a new style of Greek Church painting. Тhe founder was a professor of the Athenian school of fine arts: German artist Ludwig Trich who showed interest in Byzantine painting. He used the Byzantine program framework as the basis for church painting, while his art style was grounded on West-European principles. His pupil, Litras, the best Munich academy graduate, became a follower of this direction, while he was simultaneously engaged in secular painting.

Defeat in the war with Turkey in Asia Minor in 1922 and loss of primordial Greek territories introduced new realities into the life of the country. The ‘Great Idea’ was abandoned and the national spirit experienced pain, causing nihilism to affect Greece’s self-consciousness. The following twenty-year period is the most intensive and fruitful in its history of art. The main characteristic of this period is the deep interest to understand its own roots, to seek Greek traditional values and re-think them anew. Byzantine culture and art as the nostalgic reflection of the ‘Great Ideas’ gained special interest, respect and love. Fotis Kontoglou (1896-1965), a refugee from Asia Minor, painter, writer and teacher, preached the revival of Byzantine art through his work and based his own creative quest on Byzantine painting as a form of thought, with its characteristic materials and style. This newly revived style soon became the official trend in the Greek Orthodox Church.

.jpg)

Fotis Kontoglou

Russia

Disintegration of the common orthodox space as а consequence of the downfall оf the Byzantine Empire had its negative influence uроn the Russian church as well, and, naturally, on the development оf Russian church painting. Fierce disputes about the role and place of the church, which began inside the Russian church in the 16th century, Ñаmе to an end with the reforms introduced bу Peter I (1672-1725) when the patriarchal institute was abolished in Russia and the church was entirely subordinated to the state. Peter’s desire to form the Russian state after the example of European countries was echoed by the tendency to form Russian artistic thought after the aesthetics and principles of West-European painting. Gifted Russian painters were sent to West Europe fоr education. In 1757 the Russian Roya1 Academy of Arts was founded, which helped in the formation of а new style.

In the 17th century the process began of separation between church painting and secular painting, which terminated in the 18th century with the pre-dominance of secular painting. Ву this time church painting had turned into а second-rаtе artistic sрherе, not еvеn rеgаrdеd as art in the sense of high art. The traditional artistic way of thinking is forgotten and church painting was filled with а spirit of western artistic aesthetics.

Incompatibility of а state system and religious thought became quite obvious in the beginning of the 19th century. Vigorous Slavophil ideas about Russia's mission as a country of Orthodox faith intensified interest in the Old Christian Russia and Byzantium. Discussions about sacralization of the еmреrоr and the idea of unification of church and state called forth an image of a Byzantine Basileus. In addition West-European scholars themselves showed growing interest in medieval Christian Art.

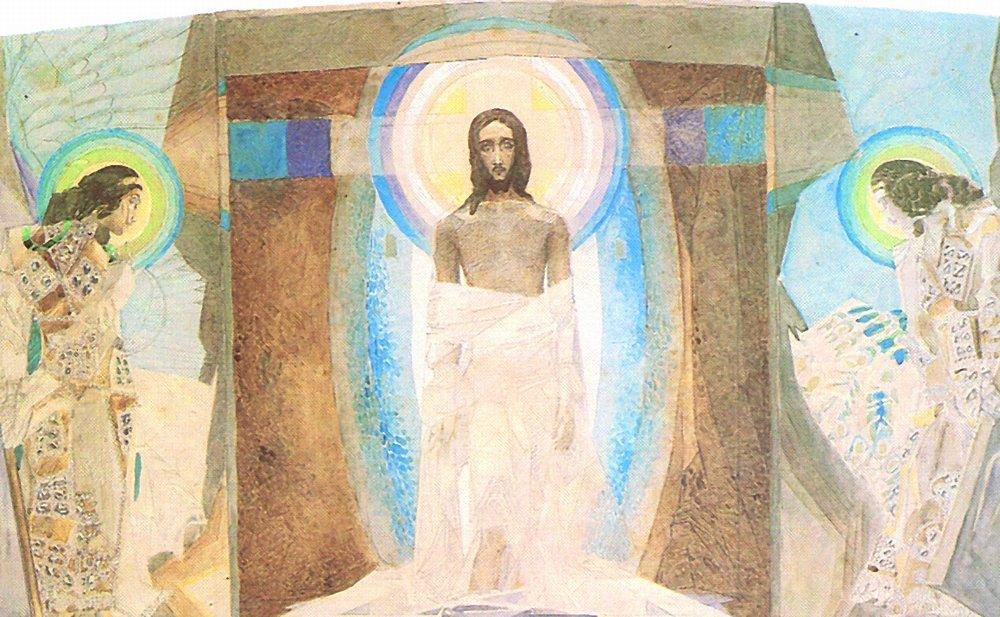

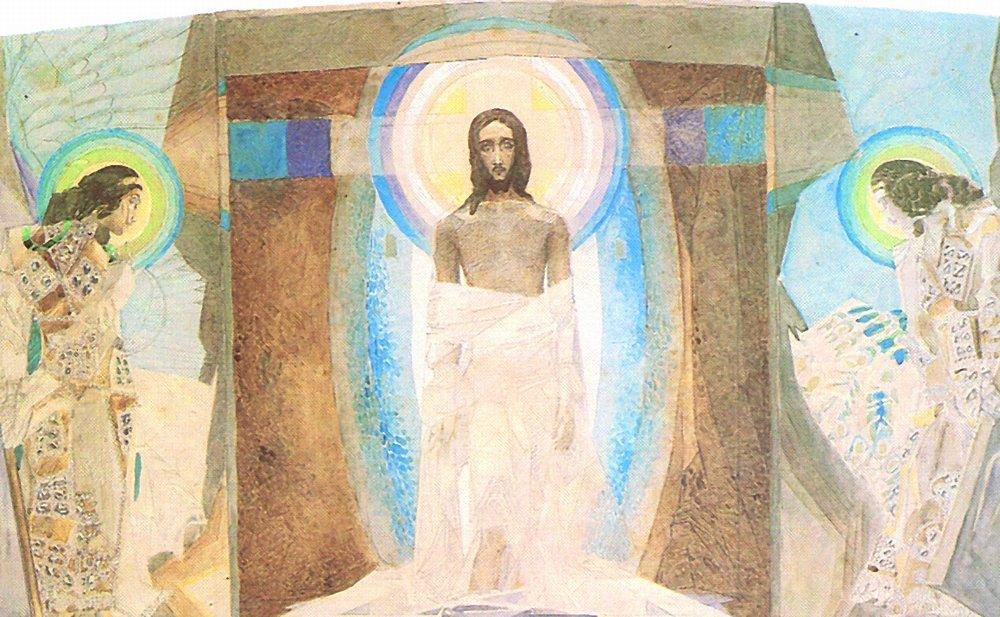

The foundation of а new school of religious painting appeared on the agenda. The first wave of such attempts came in the ’50s – ’60s of the 19th century. The painters Bruni and Роn Neff started to work in the sphere of church painting. In the ’90s of the 19th century a second wave in this direction took place in Russian church painting (V. Vasnetsov, Ðœ. Nesterov, Ðœ. Vrubеl). By that time the traditional heritage had become better studied, though still only its historical aspects. Now the forgotten Byzantine art style and system became the object of wide ranging historical and theoretical studies, though descriptive language was once again based on Western art values.

.jpg)

Viktor Vasnetsov

Mikhail Vrubel

Mikhail Vrubel Eаr1у 20th-century publications of theoretical works on icon painting bу Е. Trubetskoy (1915) аnd Р. Florenski (1922) suggest that bу this time Russian society had come vеrу close to a рrоfоund understanding of traditional church painting, and was able again to disclose its innеr character. However, the historica1 developments of 1917 interrupted the natural course of development in the church painting.

Georgia

In consequence of the disintegration of the common Orthodox space and disastrous historical situation, traditional church art started to decline in Georgia by the middle of the 18th century. Traditional art was gradually replaced by West-European aesthetic principles. The process of demarcation between church painting and secular painting was started.

The 19th century was marked by loss of state independence, the autocephaly of the Georgian church, and subjection to the Russian empire. Russian influence respectively prevailed. Georgian monumental church painting of the first half of the 19th century, due to the absence of а professional art schools, is represented bу amateur painters and reveals features characteristic of traditional art combined with features of westегn painting.

The growing interest in church painting in Russia in the latter half of the 19th century and its ‘Neo-Byzantine’ dispositions touched Georgia as well. Professional Georgian painters of European breed did not appear until the ’80s – ’90s of the 19th century. Foreign painters with a higher education who lived or came to work in Georgia (G.Gagarin, K. Kolchin, L. Longo) started to work in the sphere of church painting. Simultaneously there was a circle of amateur painters.

.jpg)

Grogori Gagarin

In 1873 an art school was established in Tbilisi and in the 1880s - 1890s the first generation of artists with higher education appeared in Georgia. The newcomers had to overcome backwardness in the development of Georgian artistic creativity in comparison with Europe and Russia, and to take upon themselves the very important and difficult responsibility of laying the foundations for a new Georgian painting. Georgian artists had lagged behind in the advanced artistic developments of the 19th century, but these artists helped a new generation of artists to solve the new tasks.

The reactionary politics of Russia in Georgia made it necessary for the Georgian society to protest in order to defend its national dignity. Georgian patriotistic activity gave rise to a national consciousness among the Georgian civilian society and clergy since the 1860s. In the beginning of the 20th century two very important events took place in Georgian history – the restoration of autocephaly of the Georgian church and the declaration of Georgian’s independency in 1918.

At the beginning of the 20th century a young generation of Georgian painters (D. Shevardnadze, L. Gudiashvili, V. Sidamon-Eristavi, etc.) came forth. In this period Georgian fine art corresponded to advanced contemporary western artistic approaches. The historical and political situation in Georgia accounted at the same time for the special actuality of national themes in Georgian art.

The public activization of the Georgian clergy in due course brought the involvement of Georgian professional artists in church painting. Three groups of painters working in church painting can be distinguished at the beginning of 20th century: 1. Foreign painters having professional education (Nesterov); 2. Local self-educated painters (Zaziashvili); 3. Professionally educated Georgian painters (D. Shgevardnadze, V. Sidamon-Eristavi).

Dimitry Shevardnadze

This means that in the 20th century the third group (Georgian professionals) was added to the two groups of painters who had been active in the 19th century. From the point of view of technique church painting in the beginning of the 20th century remained true to oil painting. As to its programs the Byzantine traditional system of programs was followed. As to style this painting is very varied (G. Zaziashvili – 19th-century realistic art tendencies; N. Andreev – academic art; M. Nesterov – 19-20th centuries romantic and modernistic features; D. Shevardnadze – German romantic and modernistic approach; V. Sidamon-Eristavi – late 19th-century Russian modernistic influence). Thus the stylistic features of church painting reveal general tendencies prevailing in contemporary secular art in general.

It can also be regarded as a distinctive feature found within the present study that the iconic images of Georgian saints depicted in Gobron Sabinin’s book Georgian Paradise (representations of saints in the church of the Virgin’s Assumption at Shiomgvime painted by Andreev; The icons of St. Nino, St. Ketevan, St. David the Builder in Telavi Church executed by Sidamon – Eristavi; St. Ketevan’s icon from Chiatura chancel-barrier, painted by Shevardnadze) have been made new canonical examples for Georgian church painters of that time.

Together with the above said tendencies, a very important feature of the church painting of the period is a desire to show and emphasize issues related to national originality, which in its turn implies the necessity of the study and assimilation of Georgian traditional art. It is no accident that along with church painting artists (Hrinevski, Shevardnadze, Sidamon-Eristavi) were actively engaged in the study and preservation of old Georgian fresco paintings. It is also interesting that at the beginning, in the first decade, the Georgian heritage was a concern of some individuals (H.Hrinevski, D. Kakabadze) and of personal co-operation among scholars and artists ( Ekvtime Takaishvili and Dimitry Shevardnadze). In 1916 The Society of Georgian Artists was founded by D. Shevardnadze and this became the basis of very important collective expeditions with the purpose of the investigation and copying of Georgian Christian fresco paintings.

The establishment of the Communist rule in 1921 in Georgia unfortunately made subsequent development of these very interesting processes in Georgian church painting impossible.

.jpg)

Henrik Hrinevski

Conclusion

In conclusion it may be said that by the early 19th century the traditional church painting in Greece, Russia and Georgia had fallen into oblivion, but from the middle of the 19th century a history begins of new church painting that lasts until the early 20th century. Talented artists with a classical European art education took part in this process. The forgotten Byzantine art style and system became the object of wide ranging historical and theoretical studies, though descriptive language was once again based on Western art values.

The 20th century brought a serious challenge to most Eastern European Christian countries, which were subjected to Bolshevist rule. It was the Church that was subjected to the most persecution under this regime. Consequently the continued development of Christian art – some isolated cases apart – was hindered. The only important Orthodox Christian country left outside of the Soviet regime was Greece where, in spite of difficult political cataclysms, ecclesiastical art continued to develop and by the 1930s the essence of traditional Orthodox Church painting – as to materials, techniques and symbolic content – had been revived.

********

Anna Mgaloblishvili is a Georgian painter and art historian. She studied painting at the I. Nikoladze Art College and the Tbilisi State Academy of Fine Arts, where she was part of a group of students who established an experimental studio of Church Murals and Icons. It was one of the first attempts to bring church art into the university after the fall of the soviet rule in Georgia. She has regularly participated in exhibitions in Georgia and abroad and was curator of several art projects. She has taught painting at the I. Nikoladze Art College, worked as an illustrator with various magazines and as scientific researcher at the G. Chubinashvili Institute of Georgian Art History. In 2004 she received her Ph.D. in art history. Her thesis was about the development of church painting in Georgia at the beginning of the 20th century (1900-1921). Her study made a comparative analysis of Georgian church painting with the traditions of other Orthodox countries (Greece, Russia). Since 2006 she is an assistant professor of the Department of Art History and Theory at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts and since 2008 she is one of the supervisors of the research direction Religious Art in the Modern World.

This article is part of the manuscript in progress: Anna Mgaloblishvili: Church Painting at the Beginning of the XX Century in Georgia (1900-1921).