Dali, Salvador - VM - Reinier Sonneveld

A Four-dimensional Jesus

by Reinier Sonneveld

Two of the most famous painters of the twentieth century were serious Catholics: Andy Warhol and Salvador Dalí. Warhol was a regular volunteer among the homeless and visited the mass almost daily, but kept this painstakingly hidden. Dalí was more open about it and for instance illustrated a Bible edition with more than hundred watercolours (Biblia Sacra, 1963-1964).

Dalí was Catholic by birth, but started taking his faith seriously only after World War II. Although he continued to make art for more than 40 years after the war, this period tends to be somewhat spirited away among art historians. This is also due to his great renown as a Surrealist: the empty planes, the dripping clocks, the elephants on stilts. Surrealism sought a kind of redemption in dream images, but the atom bombs on

He first published a pamphlet, in which he – in his characteristic bombastic and flamboyant manner – defined himself as a ‘nuclear mystic’. From then on he wanted to find his inspiration in contemporary scientific discoveries and Classicism with its precise rendering of the human body and carefree depiction of biblical stories. His famous Corpus Hypercubus from 1954 forms the pinnacle of this period.

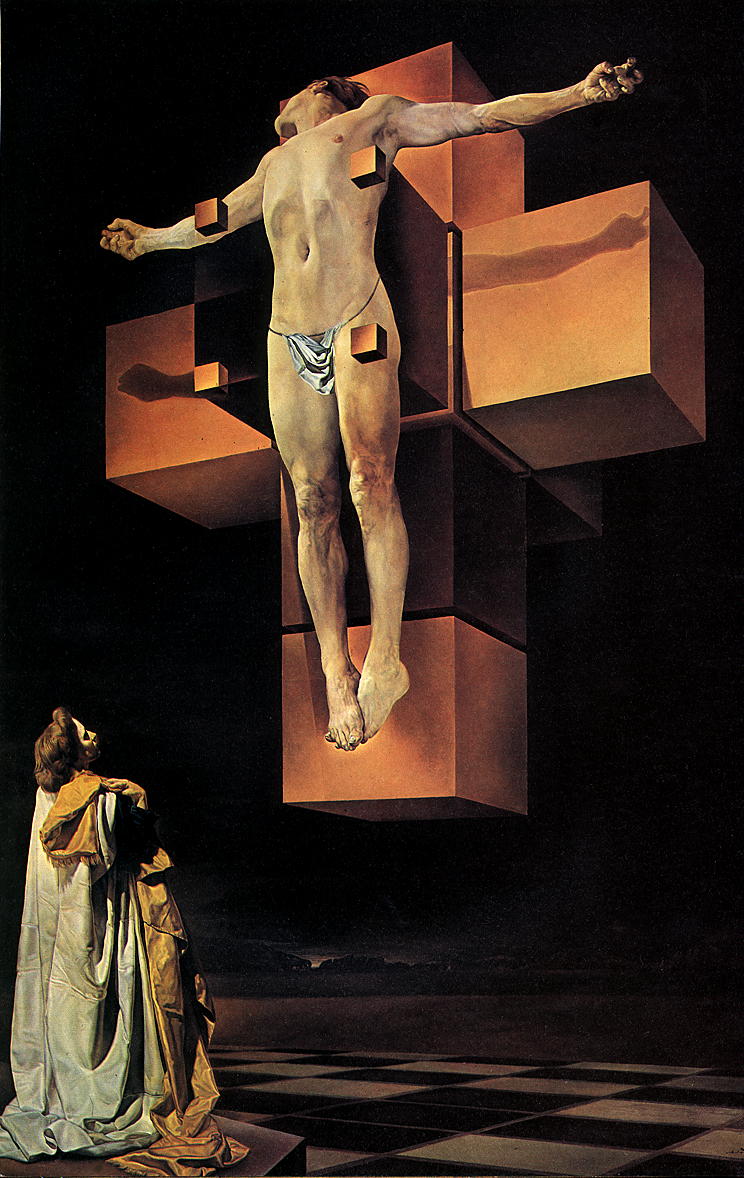

Here Dalí totally re-invents the usual Crucifixion. What stands out is that:

– Dalí does not attempt to place the event in a historical setting. Christ is floating in an almost abstract space.

– In the left lower corner you see his spouse and muse Gala as Mary Magdalene with re

– The chessboard, wherein five black squares form a cross. Possibly this is a symbol for the various roads a life can travel.

– Christ averts his head, so that we cannot look him in the eye. Is his face too holy for our gaze? Would we collapse under its weight?

– Christ has no wound in his side, no crown of thorns on his head, no nails through his hands or feet. He is undamaged, invulnerable. As if he has already risen.

– Both his knees look ‘messy’. In reproductions (like the one above) you can hardly see it, but when you stand before the original, you can recognize five images of Dalí himself in the left knee and five of Gala in the right one. As if they have been taken up in Christ’s body.

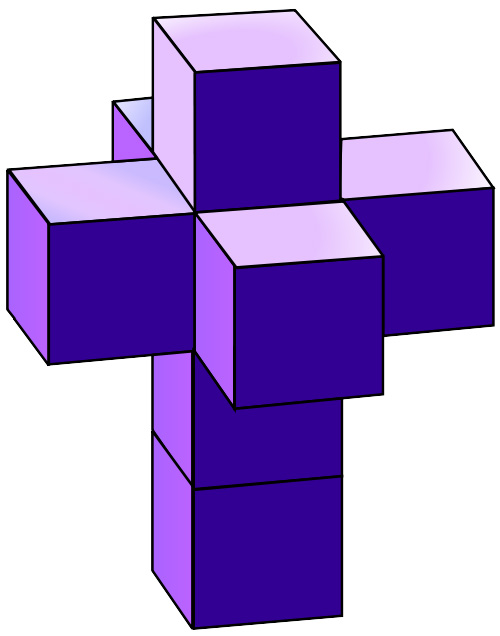

But the most striking is of course the cross. The title Corpus Hypercubus hints at its meaning. A hypercube is a four-dimensional cube. The cross in the painting shows this form in its ‘unfolded’ state.

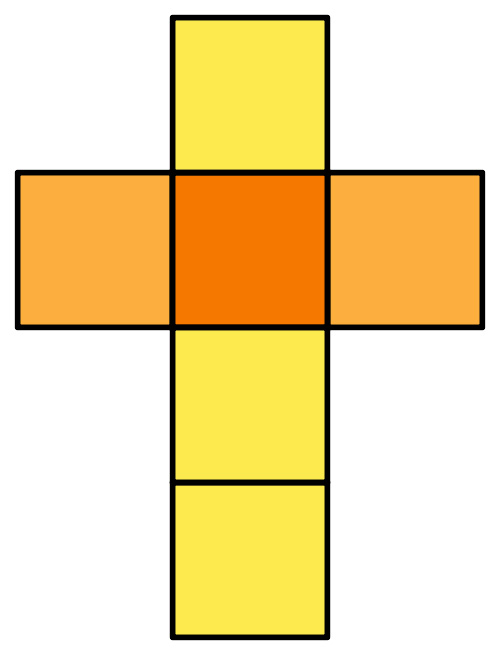

I need to explain this. As a child everyone has probably at some point folded a cube from paper. To do this, you have to cut a piece of paper like this:

You can transform this flat two-dimensional cross into a spatial three-dimensional cube. In theory you can also make a hypercube, a four-dimensional cube, in a similar way. But in reality it is not possible to fold this cube, as our world has only three dimensions (height, breadth and depth). However, the unfolded form looks like this:

This is the stage you see in Dalí’s painting. What in our reality is a symbol of suffering (the cross) can in a different reality be folded up into a symbol of perfection (a cube).

Dalí thus expresses the double meaning of Christ’s crucifixion, which already comes to the fore when John calls this drama ‘elevation’ (often translated as ‘glorification’). This is literally elevating someone onto the cross, but also figuratively that Christ has won a victory.

Perhaps this is why Dalí represents Gala in such a worthy manner and Christ without wounds. As if we are already a stage ahead. As if time does not exist here. As if we look at this from a higher reality with many more dimensions than ours, where our pain can be ‘folded up’ into perfection.

*******

Salvador Dalí, Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), 1954, oil on canvas, 194 x

Reinier Sonneveld (b. 1978) makes his living by creating short films and writing (mainly theological) books. He was the youngest writer in the

ArtWay Visual Meditation September 29, 2013