England: St Andrew Bobola in London

Church of St. Andrew Bobola, Shepherd’s Bush

by Jonathan Evens

The Church of St. Andrew Bobola, Shepherd’s Bush, is one of London’s hidden gems. St. Andrew Bobola was a Polish Jesuit missionary and martyr, known as the Apostle of Lithuania, and this Roman Catholic Church dedicated to him opened in 1961 in a former Presbyterian Church building that has been extensively restored as a living memorial to Poles who died during World War II. The church holds the main shrine in Britain to the dead of Katyn, the 1940 massacre of thousands of Polish officers by the Soviet secret police.

Alexander Klecki (1928–2014) was the architect responsible for the transformation of the building. He also created much of its interior art:

- The aluminium-on-steel Christ the King over the altar

- The figures of St. Andrew Bobola and St. Maximilian Kolbe on the east wall

- The twelve bronzed cement panels depicting the Stations of the Cross

- Ten of the stained glass windows

Given his extensive involvement with the church, it is no surprise to find that he was appointed its custodian.

|

|

In the chapel of Our Lady of Kozielsk is a bas-relief icon carved by a lieutenant in the Polish army, Tadeusz Zielinski, who survived imprisonment in the Soviet camp at Kozielsk. He carved the icon in secret into a lime-wood door plank, using for tools fragments of steel he found in the prison yard. When he was transported to a camp at Grazowiec, Zielinski hid the carving in the false bottom of his suitcase. After his arrival he added colour to the icon using paints intended for communist slogans. The icon eventually travelled to Persia, Palestine, Egypt, Italy, and finally England, where it was installed in St. Andrew Bobola’s in 1949. [1]

The skillfully integrated stained glass windows throughout the church relate to the Polish soldiers, sailors, and airmen who fought alongside the Allies in World War II. Their most distinguished leader was General Wladyslaw Anders, whose memorial fills the triple lancet stained glass window in the south transept. General Anders led the Polish Second Corps in the final push against German troops in Italy, including the heroic assault on Monte Cassino. The window depicts the crucifixion and includes the most revered Polish military decoration, the Virtuti Militari Cross.

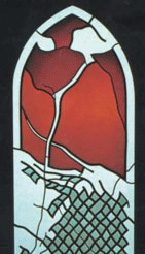

The second remarkable window – in the north transept [pictured below] – commemorates Polish airmen who fought in the Battle of Britain. This was designed by the painter Janina Baranowska, who won the competition set by the Union of Polish Airmen in 1979. . . . The window was made by the firm of Goddard & Gibbs and inaugurated by Cardinal Rubin on 3 April 1980. The three lancet windows cleverly integrate the Cross with two swooping plane trails. The composition is surmounted by the icon of Our Lady of Ostrobrama.

Another interesting window commemorates the Polish secret underground men who were trained at the SOE centre at Audley End and then parachuted into German occupied Poland. [2]

Janina Baranowska—one of the church’s stained glass artists—was born in Grodno (in modern-day Belarus) and remained there until the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1940 she was arrested and deported to Russia. Two years later she was released and joined the Polish Army in its march to the Middle East. In 1946 she moved to London, where she studied under Professor David Bomberg at the Borough Polytechnic from 1947 to 1950. For a number of years she was on the boards of the National Society of Painters, Sculptors & Printmakers and the Association of International Arts. In 1980 she became president of the Polish Artists Society in Great Britain (now the Association of Polish Artists in Great Britain) and a member of the Catholic and Christian Artists group.

Besides designing stained glass windows, Baranowska also practices painting and graphic art and has exhibited in leading galleries in the UK, France, Poland, and the United States. For the last twenty years she has been working as director of the gallery in the Polish Social and Cultural Centre (POSK) in Hammersmith in London, organizing exhibitions and helping artists from Poland and other countries. The mission of POSK is “to promote and encourage access to Polish culture in all its forms to Poles and non-Poles.”

Many Polish artists were forced to flee mainland Europe during the World War II. Some of these artists journeyed through many countries before settling in the UK, while others were captured and imprisoned before finding their way to British shores.

Marian Bohusz-Szyszko (1901–1995) was one of the key organizers in this group of artists. He organized art classes – at first in a reception camp, later at various addresses in London and finally at the St Christopher Hospice at Sydenham. The classes became known as the Polish School of Painting, and were eventually taken under the wing of The Polish University Abroad. The relatively younger artists, including Stanislaw Frenkiel, founded in 1948 the Young Artists Association. A group calling themselves Group 49 took its place a year later and mainly consisted of pupils of Bohusz-Szyszko. In 1955, with Polish artists beginning to be more successful commercially, a society was formed with the neutral title of The Association of Polish Artists in Great Britain (APA). Although APA was intended to be a broad church, the pupils of Marian Bohusz were still the most important element. [3]

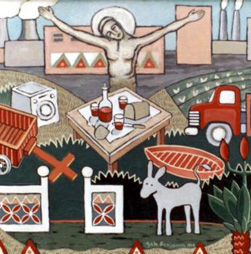

Bohusz-Szyszko and other exiled Polish artists (such as Frenkiel, Adam Kossowski, Henryk Gotlib, Marek Zulawski, and Alexander Zyw) were part of a consistent but under-recognized strand of artists utilizing sacred themes. Many of these artists were featured in the recent “Pole Position” exhibition at the Graves Gallery in Sheffield. Overtly religious paintings in this exhibition, such as Baranowska’s Crucifixion and Bohusz-Szyszko’s Christ Crowned with Thorns, are “on the anguished side of Christian art” and “agonise in brilliant, almost hellish colour.” [4]

In addition to organizations like the POSK and APA, St. Andrew Bobola’s has been a key source of support for many in the Polish émigré community. Monsignor BronisÅ‚aw Gostomski was a recent parish priest at the church who was known for working hard to support the Polish community. He spearheaded a £1 million renovation project at the church and worked to unite older and younger generations of Poles within his congregation. As chaplain of the Polish Ex-Servicemen’s Association (SPK), he cared spiritually for those who had been left in England when the dramatic events of World War II and the Cold War took their course. He also cared for those who had come to England in more recent years in pursuit of a new life and opportunities. Tragically, he was among the 96 victims of the Polish Air Force Tu-154M plane crash on April 10, 2010, which also claimed the lives of Polish president Lech KaczyÅ„ski, Polish president-in-exile Ryszard Kaczorowski, and many of the country’s other top officials and dignitaries.

With these connections St. Andrew Bobola’s commemorates not only the Poles who died during World War II, but also those who have contributed to Polish life and culture in the UK.

SOURCES:

1. Jan PieÅ„kowski, “Polish Art in W12,” Hammersmith and Fulham Historic Buildings Group Newsletter No. 21, Autumn 2009, p. 7. <http://www.hfhbg.org.uk/newsletters/Newsletter-21-Aut-09.pdf>

2. Ibid.

3. Douglas Hall, Art in Exile: Polish Painters in Post-War Britain (Bristol, UK: Sansom & Company, 2008).

4. Pole Position: Polish Art in Britain 1939–1989 (Sheffield, UK: Graves Gallery, 2014).