Gogh, Vincent van - VM - Bruce Lockerbie

Vincent van Gogh: Still Life with Open Bible

Van Gogh’s Authentic Discipleship

by D. Bruce Lockerbie

In April 2010, the Royal Academy of Arts in London presented an exhibition called “The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters.” Along with almost 100 paintings were three-dozen letters Vincent van Gogh had addressed to his younger brother Theo, his sister Willemina, or other artists.

Until then, I possessed only superficial highlights of the painter’s tortured life and mental instability. Knowing that his father had been a Dutch pastor, I knew nothing of Vincent’s own deeply earnest religious convictions—indeed, his radical Christian faith and desire to be an authentic disciple of Jesus Christ and his teachings. I was not prepared for what I was about to learn.

Of course, I was impressed by the paintings, especially his most well-known works such as Starry Night (1889). But even more fascinating were the letters in van Gogh’s own hand, accompanied by a curator’s notes. I learned that in 1875, at age 22, while teaching at a school in England, Vincent had announced his intention to prepare for ordination as a Methodist minister. He did not attend but acknowledged and admired revival services conducted by the visiting American evangelists Dwight Lyman Moody and Ira Sankey, writing to Theo (Letter #67, May 1876), “It is touching to see the thousands of people listening to the evangelists.” Another notice referred me to the text of his first sermon, preached in October 1876. I discovered that he left England to enroll in a Belgian seminary, but soon withdrew to become an evangelist, ministering primarily to miners and their families in the Borinage district. He declared his call by God to Theo (Letter #77, October 1876), quoting from Isaiah: “He has sent me to preach the Gospel to the poor.”

Van Gogh was zealous, giving away his possessions—even most of his clothes—to his needy parishioners. Pious superiors regarded him as excessively fanatical, even obsessive, and so the leaders of the Reformed Church dismissed him as unfit for the ministry. By 1880, van Gogh had abandoned the Church that had abandoned him. In place of its rigidity he experienced a “conversion to art,” as he called it. From then on, his “sermons” would be proclaimed by his paintings.

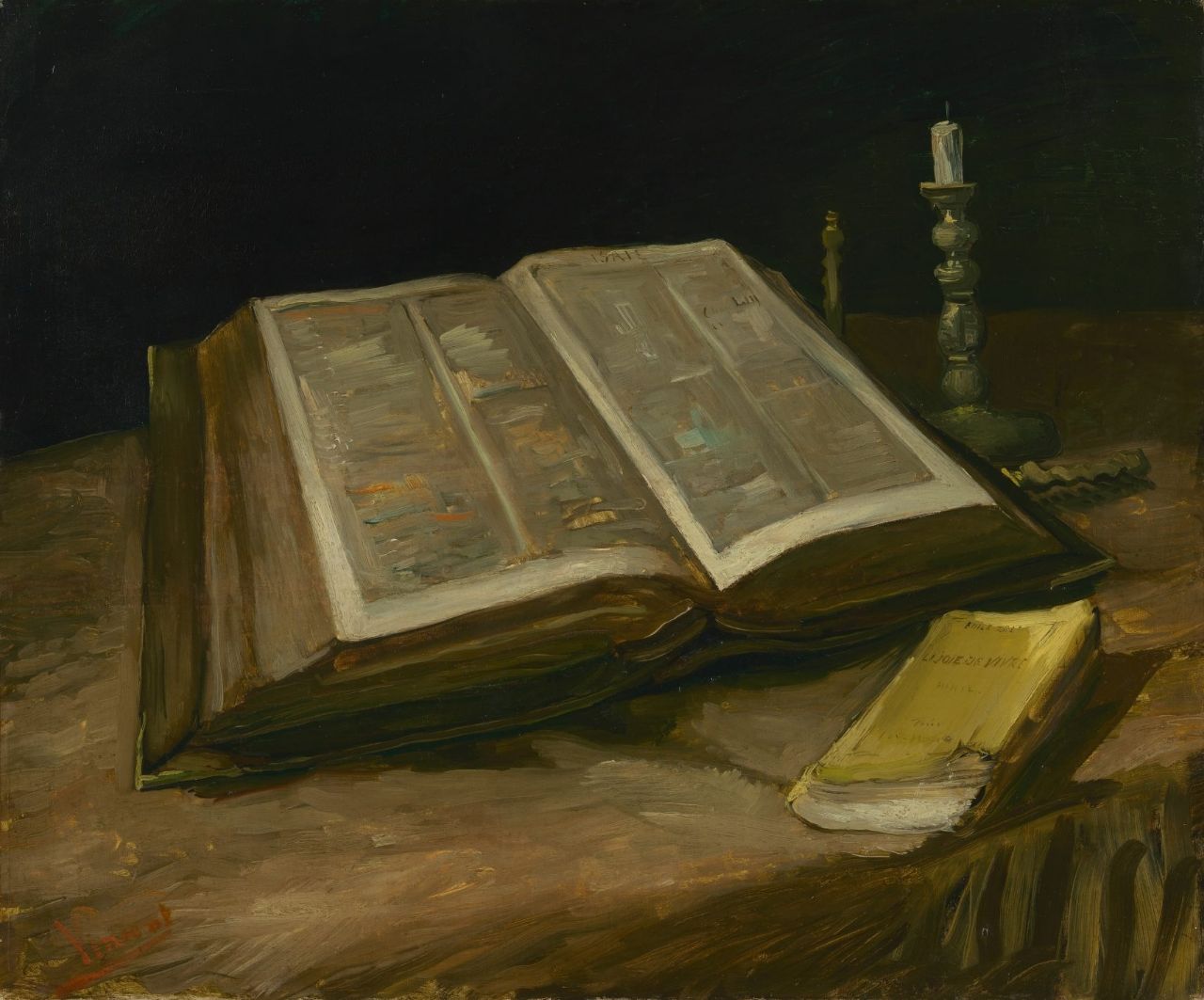

Thus newly informed I came upon one of the most telling paintings, Still Life with Open Bible, completed in 1885, a few months after the death of his father with whom he had a stormy relationship. On a draped table a large family Bible lies open to Isaiah 53, although its text is unreadable. To the right of the Bible stands a candlestick, its flame extinguished, while in the forefront lies a copy of Emile Zola’s 1884 novel Joie de Vivre (“Joy of Life”). The burned-out candle sheds no light on the Bible’s pages, yet from some other source a glow shines upon and from the contemporary novel.

This painting powerfully reveals diametric opposites suggested by the Bible’s darkened message and by Zola’s sensual alternative version. By conflicting realities and contrasting ironies, the painter offers both “this so saddening Bible” (Letter #632 to Emile Bernard) and Zola’s misleading hedonism.

Yet I do not accept that this painting declares any final demitting of religious faith by Vincent van Gogh. Instead, he lived his remaining five years in a conflicted state of mind, heart, and soul. Outwardly a rebel against the Church that had rejected him, he remained a student of the Bible and especially of its modern application. His letters make clear that—however unconventional or even distorted his understanding of Scripture—his worldview was shaped in large part by his reading and absorbing the message of the Gospel and its application to real life.

In Lettter #543, September 1888, he confesses to Theo that whenever he may feel a “terrible need of— shall I say the word, religion—then I go out at night to paint the stars.” By communing with the night sky he felt a greater proximity to the God he once sought to serve as a missionary-preacher than when debating with other clergy the scruples of their theology and his calling to authentic discipleship.

*******

Vincent van Gogh: Still Life with Open Bible, 1885, oil on canvas, 65.7 x 78.5 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent Willem van Gogh (1853-1890) was a Dutch post-impressionist painter who posthumously became one of the most famous and influential figures in the history of Western art. In a decade, he created about 2,100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings, most of which date from the last two years of his life. They include landscapes, still lifes, portraits and self-portraits and are characterized by bold colors and dramatic, impulsive and expressive brushwork that contributed to the foundations of modern art.

D. Bruce Lockerbie is an American educator and Chairman/CEO of PAIDEIA, Inc., an international consulting agency (www.paideia-inc.com). He is author or editor of more than 40 books; his interest in the relationship between the arts and biblical faith is well represented by several of those titles: The Liberating Word: Art and the Mystery of the Gospel, The Timeless Moment: Creativity and the Christian Faith, and Dismissing God: Modern Writers’ Struggle against Religion. During a college lectureship in the late 1970s he met sculptor Ted Prescott and their interaction contributed to the shaping of Christians in the Visual Arts (CIVA). He was first introduced to the Artway Visual Meditations by his friend Laurel Gasque (ArtWay Associate Editor).

ArtWay Visual Meditation August 8, 2021