Sahi, Jyoti - by Victoria Emily Jones 2

The Art of Jyoti Sahi: Jesus the Dancer

by Victoria Emily Jones

Our Lord is the Dancer, who, like the heat latent in firewood, diffuses His power in mind and matter, and makes them dance in their turn. Tiruvatavurar Puranam (stanza 75), a 15th-century sacred text written by Kadavul Mamunivar; translated by Nallasvami Pillai

The Supreme Intelligence dances in the soul . . . for the purpose of removing our sins. By these means, our Father scatters the darkness of illusion (maya), burns the thread of causality (karma), stamps down evil (mala, anava, avidya), showers Grace, and lovingly plunges the soul in the ocean of Bliss (ananda). They never see rebirths, who behold this mystic dance. Unmai Vilakkam,vv. 32, 37, 39

The ‘Lord of the Dance’ or ‘Nataraja’ in the Shaivite tradition, is the Creator who is both a giver of life, but also a destroyer of all that stops us from being set free. He carries the fire of destruction and transformation, while at the same time assuring his disciples that they should not fear, and beating the drum of the rhythms of the Cosmos. As he dances he steps across the demon of darkness and blindness, showing the way to a new life. Jyoti Sahi

In this article I will explore how Hindus perceive of Shiva as Lord of the Dance, and then consider how we might apply a similar characterization to Jesus, as does Indian Christian artist Jyoti Sahi in his woodcuts and paintings. First, though, it's important to note that not all the characteristics of the dancing Shiva can be said to belong to Jesus—some are flat-out contradictory to Jesus’ nature (Shiva’s aimlessness, for example; his “oneness” with creation; and so on), and some are just irrelevant, with no clear parallel. I am being purposely selective for the sake of focus.

Try not to get too bogged down by the foreign words and symbols. Just let Sahi’s art be your guide through this discussion. He is one of my favorite artists, and although some background information will likely enhance your appreciation of his art, you can still enjoy the art without it.

Shiva as Nataraja

In the Shaivism sect of Hinduism, Shiva (Sanskrit for “Auspicious One”) is revered as the supreme god, who performs five cosmic functions: Creator, Preserver, Destroyer, Concealer, and Revealer. (In other sects, these first two roles are filled by Brahma and Vishnu, respectively.)

Shiva also has different embodiments, one of them being the Nataraja (“Lord of the Dance,” or “King of Dancers,” in Sanskrit).

Shiva as the Lord of Dance. c. 950-1000. Copper alloy. Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The earliest known depictions of Shiva as Nataraja are from the tenth century. He is shown with four arms: one holding a drum, one holding a flame of fire, one positioned palm-out, and one gesturing toward his uplifted foot. His dance is called the Tandava, and it is the source of all movement in the universe. Shiva dances to release the souls of men from ignorance and illusion, personified by the mythological dwarf demon Apasmara, whom he crushes underfoot.

The symbolic significance of the Nataraja is described in the Chidambara Mummani Kovai, a Shaivite scripture:

O my Lord, Thy hand holding the sacred drum has made and ordered the heavens and earth and other worlds and innumerable souls. Thy lifted hand protects both the conscious and unconscious order of Thy creation. All these worlds are transformed by Thy hand bearing fire. Thy sacred foot, planted on the ground, gives an abode to the tired soul struggling in the toils of causality. It is Thy lifted foot that grants eternal bliss to those who approach these. These Five-Actions are indeed Thy handiwork.

Another sacred Hindu text, the Unmai Vilakkam, offers this more succinct description: “Creation arises from the drum: protection proceeds from the hand of hope: from fire proceeds destruction: the foot held aloft gives release.” (This description leaves out Shiva’s fourth act.)

Jesus, too, creates, protects, destroys, and releases. That’s why Sahi draws on the iconography of the Nataraja in his depictions of Jesus as a device for contextualization.

Jesus as Creator

Hindus consider creation to be a part of God’s play. According to Hindu cosmology, Shiva danced the cosmos into being, and he continues to sustain it by dancing. In his upper right hand, Shiva holds an hourglass-shaped drum, on which he beats the pulse of the universe.

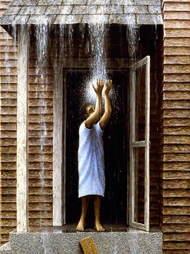

Jyoti Sahi, 1978. From the Psalm Series. Published in The Holy Waters: Indian Psalm Meditations, Asian Trading Corporation, Bangalore, 1984

In the woodcut above, Jyoti Sahi portrays Jesus as Creator. Jesus beats a drum, expressing his creative joy. He dances creation into existence.

We tend to think of God the Father as Creator, but John 1:1-10 reminds us that Jesus created too. Verse 3 says, “Through him [Jesus] all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made.”

Not only did Jesus create the material world, he creates new hearts in all those who call on his name (Psalm 51:10). And the time will come when he will create the whole world anew: “Behold, I will create new heavens and a new earth. The former things will not be remembered, nor will they come to mind. But be glad and rejoice forever in what I will create, for I will create Jerusalem to be a delight and its people a joy” (Isaiah 65:17-18).

Jesus as Protector (Preserver, Maintainer, Sustainer, Support)

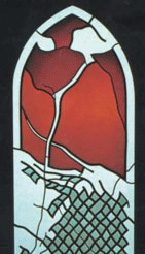

Jyoti Sahi: Dancing on the Water

As Nataraja, Shiva’s lower right hand is held in the abhaya-mudra (“abaya” = “fearlessness”): right hand raised to shoulder height, arm bent, palm facing outward, and fingers upright and joined. This gesture signifies protection, peace, and the dispelling of fear.

Throughout the Christian Scriptures, God is referred to as his people’s Protector, Defender, Shield, and Help. Jesus certainly embodied these traits, as he gave voice to the voiceless, and strength to the weak.

Our call to salvation is a call to power and rest. Jesus wants us to lay aside all our fears and trust in his divine protection. The command “fear not,” or “be not afraid,” is a common one throughout both testaments. Here’s just one example:

When evening came, his disciples went down to the lake, where they got into a boat and set off across the lake for Capernaum. By now it was dark, and Jesus had not yet joined them. A strong wind was blowing and the waters grew rough. When they had rowed about three or four miles, they saw Jesus approaching the boat, walking on the water; and they were frightened. But he said to them, “It is I; don’t be afraid.” Then they were willing to take him into the boat, and immediately the boat reached the shore where they were heading. (John 6:16-21)

Jesus as Destroyer (Transformer)

You might be averse to the notion of a god who destroys, but Hindus understand destruction as a necessary counterpoise to creation, as something that helps maintain the harmony of the cosmos. That’s why Shiva holds fire in his upper left hand, opposite the drum—to signify this balance between creation and destruction. Hindus don’t see Shiva’s destructive function as scary or evil, for he is on their side, destroying all obstacles that stand in the way of their liberation. Shiva’s fire not only destroys but cleanses and transforms as it blazes open a path to release. For this reason, his destruction dance is every bit as joyful as his creation dance.

Tradition says that Shiva dances the Tandava in cemeteries and burning grounds. But he also dances on the burning-grounds of the heart, the place where illusion and ego are burnt away. A Bengali Hymn to Kali, the feminine manifestation of Shiva, says, “Because you love the burning-grounds, / I have made one of my heart, / that you may dance therein your eternal dance.”

I like the picture of my heart being a site of cremation—where God burns away my sin, reduces it to ashes, every time I die to self. Jesus is an easy parallel to this aspect of Shiva: at our request, he destroys all obstacles that keep us from knowing his true nature and our own. Jesus makes debris of our defense walls, melts down our chains of sin and death, and then rebuilds us. He breaks and he makes whole. From his destruction proceeds creation.

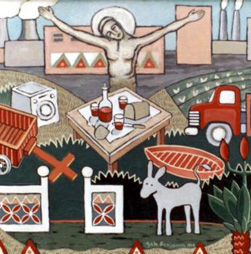

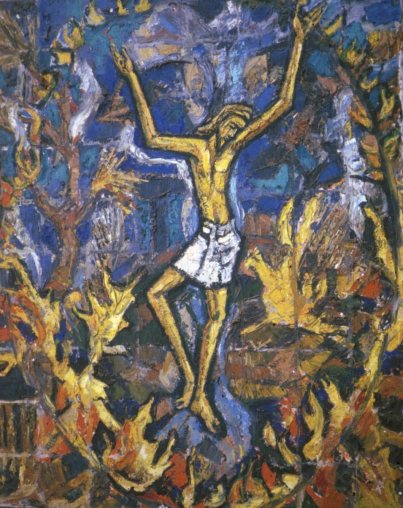

Jyoti Sahi, Lord of Dance, 1980. Oil on canvas

I think of the destructive act of Christ’s crucifixion. Christ was devastatingly crushed on the cross. Yet something new and glorious proceeded from his (temporary) destruction: the possibility of salvation for all mankind. In Sahi’s painting, the crucified Jesus is circumscribed by flames of agony, which lick the air around him. But these flames transform even as they destroy. The choreography of the cross consists of a submissive pose—arms outstretched, head hung low—but one that, after a few measures of rest, transitions into steps of renewed vigor. (Can you hear the drumbeat?) The crucifixion was all part of the great cosmic dance that sustains all things. Just as surely as Jesus “destroyed the temple,” so to speak, he surely raised it (Matthew 26:61), and not only that, he raised generations upon generations of saints to God. (More on this below.)

Jesus as Concealer? (Suppressor, Illusion)

I’m not sure I understand the meaning of this divine aspect (the passages on it are very sparse, and those that I did find are difficult to interpret), but from what I’ve been able to grasp, it doesn’t seem to mesh well with Christian theology. Yahweh is a God who loves to reveal himself, and the Christian Bible is the story of how he did that over a period of 2500+ years.

Perhaps a loose comparison might be made to the incarnation act of God. When he was born on Earth as Jesus, God had to veil part of his glory and limit his power. Paul tells us in Colossians 2:9 that “in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form,” but that fullness was not made manifest; it was hidden, to be revealed at a later time.

One exception, though, was at the Transfiguration, when Peter, James, and John saw Jesus for who he was in full.

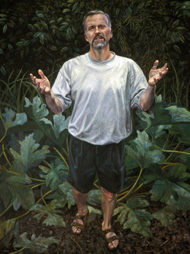

Jyoti Sahi, The Transfiguration, 2000. Oil on canvas

Jesus as Liberator (Revealer, Releaser, Savior, Blesser, Bestower of Grace)

Shiva’s upper left hand makes the gaja-hasta-mudra (the posture of the elephant trunk), which symbolizes his power to remove all obstacles on the path to liberation. It gestures toward his raised left foot, which represents liberation, grace, uplift.

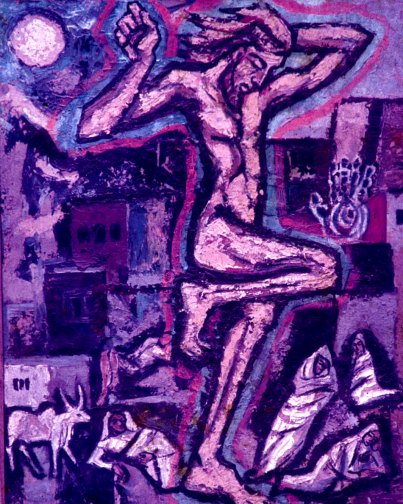

Jyoti Sahi, He Who Steps Over—The Tandavan, 1975. Oil on canvas

In He Who Steps Over—The Tandavan, Sahi depicts the resurrected Christ stepping over the sleepers who lie outside his tomb. “The Tandavan” is just another name for the Nataraja, meaning “he who steps over.” Think of all the “stepping over” Jesus did: first he stepped over to Earth, then he stepped over to death, then he stepped over to hell, then he stepped back over to life, then he stepped up to heaven. Because Jesus graciously bore the destruction due us, we can now follow him in the last two steps; we, too, can step over to the other side.

Conclusion

I’d like to close with an excerpt from a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, an early twentieth-century Bengali writer:

Let the links of my shackles snap at every step of thy dance,

O Lord of Dancing,

and let my heart wake in the freedom of the eternal voice.

Let it feel the touch of that foot that ever sets swinging the

lotus-seat of the muse,

and with its perfume maddens the air through ages.

Rebellious atoms are subdued into forms at thy dance-time,

the suns and planets, anklets of light, twirl round thy moving feet . . .

The opening image is as much aural as it is visual: Think prison cell. Or chain gang, perhaps. God is dancing (both on high and in your soul), as he has been for eternity. But now, you feel the rhythm, and you respond. You start to hear a clank, crack, clunk of your chains, breaking link by link. You are free.

Even though this poem was written in a Hindu context, I feel moved by it, as a Christian. It reminds me of that weighed-down feeling I had before I came to know Christ, when I was enslaved by sin, and of the joy and freedom that became mine once I took those initial steps into salvation. I still forge new links—of worry, of bitterness, of selfishness, and so on—but Jesus still dances, breaking through them yet again, making me light yet again. It’s an ongoing process.

This poem is a prayer that contains both supplication and praise. God, please continue your saving work in me, the speaker says. Let me feel the ground vibrate with each step of your dance.

I like how Tagore describes the sun and planets as God’s anklets, which twirl and orbit as he dances. How huge our God is! These massive planetary bodies dance to his beat, but so do the smallest of atoms—they strike poses and take on forms according to his leading. And this same God who has power over the cosmos incarnated himself as a man, so that he could dance his death-dance, or rather his victory-over-death dance, and liberate this world from bondage.

Jesus is my Lord of the Dance.

*******

Dr. Jyoti Sahi studied art at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in England and gained a Doctorate in Divinity from Serampore College. In 1970 he came to live in Bangalore where he was connected with the National Biblical Catechetical and Liturgical Centre founded by the Catholic Bishops Conference of India, soon after the Second Vatican Council, to reflect on the relation of the Church in India to Indian cultures and spirituality. He also designed works for Indian churches. Coming from a mixed religious background having Hindu and Christian roots, Jyoti has spent the last forty years trying to see how it is possible to bridge/integrate these religious and cultural divides through art. He is particularly interested in the relation of Christian symbols and stories to the sacred images that are found in other faith traditions, particularly in the Indian tradition. As an artist, he has been actively involved with various non governmental groups in India concerned with social change. Jyoti currently teaches in seminaries all over India, lecturing on the relation of art to Indian aesthetics and spirituality. Publications:

Jyoti Sahi, Stepping Stones: Reflections on the Theology of Indian Christian Culture, Asian Trading Corporation, 1986.

Jyoti Sahi, Holy Ground, A New Approach to the Mission of the Church in India, Jyoti Sahi, Asian Christian Art Organization, 1998.

Jyoti Sahi & Eric Lott, Faces of Vision: Images of Life and Faith, Christians Aware, 2008.

Victoria Emily Jones lives in the Boston area, where she works as an editorial assistant at Shambhala Publications, Inc., a publisher of books on Eastern religions, philosophy, and art. In 2010, she received a BA in journalism and English from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A year later, she founded thejesusquestion.org, a website where she explores various conceptions of Jesus in the visual, literary, performing, and musical arts, as well as in popular culture and in churches around the world.