Good Friday - Crucifixion Matthias Grünewald 2

Matthias Grünewald: Crucifixion

The shame of the cross?

by Nigel Halliday

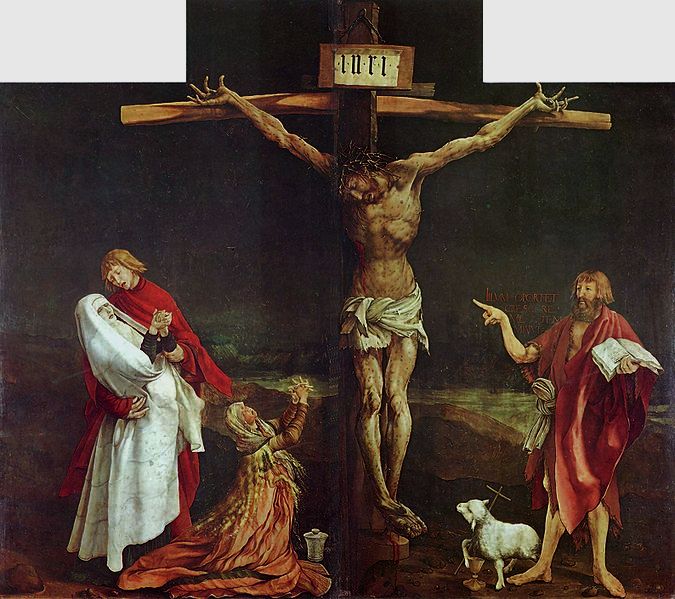

This Crucifixion by Matthias Grünewald is part of the Isenheim altarpiece, one of the great works of Western art, but less well known than it should be because it is located rather out of the way in Colmar in eastern France. The altarpiece as a whole has been discussed in ArtWay by Laurel Gasque. In this article I want to focus only on the Crucifixion, and in particular the figure of John the Baptist.

Painted c. 1512–16 the Crucifixion stands in contrast to the decorative, neo-Platonic images being produced at the time by Raphael and others in High Renaissance Italy, where Jesus is scarcely marked, apparently falling asleep rather than suffering an agonizing death, while angels on conveniently placed clouds collect small drops of blood in chalices.

Grünewald instead emphasises the pain and degradation to which our Lord submitted. Jesus’ figure is grotesque, dirty, and covered in wounds. The bones seem to be dislocated. The fingers are arced in pain. The body is pierced with painful spikes, presumably broken from the whip. Jesus’ loin cloth is tattered. Even the cross itself is twisted.

The altarpiece was made for the chapel of a monastery in Isenheim, near Colmar, which belonged to the order of St Anthony, an order founded to provide hospital care for those suffering from ergotism, a horrible skin disease. Among its many symptoms were fluid retention, ulcers, gangrene, and a burning sensation in the skin so strong it was known as Hell’s Fire, although, because of the particular devotion of the monks, it came to be known also as St Anthony’s Fire.

In the Crucifixion the artist was undoubtedly wanting to emphasise Jesus’ sympathy for the sufferers. Jesus did not turn away from them as many of their contemporaries would have done. Instead of being shown high up on a cross nearer heaven than earth, here he is almost touching the ground, down among those who worship him. And he is disfigured in the same way that they are.

The arrangement of figures around the cross is also unusual. Images of the crucifixion usually showed Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene and John the Evangelist grouped symmetrically at the foot of the cross, as Grünewald did in another version of this subject now in Karlsruhe (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tauberbischofsheim_Altarpiece).

But in the Isenheim altarpiece the artist has grouped all these figures to the left, where they respond in various states of grief. To the right is the figure of John the Baptist. His is an unexpected presence, because the New Testament is clear that John the Baptist had been executed by Herod one or two years before the Easter events. So his presence here is clearly to make a point.

And this point seems to be in the words that John is saying, which are written next to him. Usually John is associated with the words spoken to his disciples in John 1, ‘Behold, the Lamb of God,’ as he literally points to Jesus and fulfils his task as the last of the Old-Testament prophets, identifying the coming Messiah as the great sacrifice for our sin. This identification is made here visually by the lamb shown at John’s feet, whose blood pours into the chalice.

The words he speaks here though are ‘Illum oportet crescere; me autem minui,’ meaning ‘He must become greater; I must become less.’ These are from later in John’s Gospel (John 3:30), where the Baptist likens himself to the best man at a wedding. He has prepared the way for the bridegroom. Now the groom has appeared, it is his day, and the best man needs to fade out of the picture.

What particularly struck me here is that John is shown speaking the words while pointing to the crucified Jesus. The crucifixion was intended not just to kill Jesus, but to bring shame on him in so doing. More humane and honourable forms of execution were available, but crucifixion was intended to show how much the Romans and the Jewish leaders despised Jesus and how vehemently they rejected him.

However, in the scheme of God’s plan of salvation, instead of suffering shame Jesus was rewarded with honour. Hebrews 12:2 describes Jesus as ‘scorning the shame of the cross.’ Shame means contempt but it only works if the victim shares the values of the ones trying to shame him. Shame involves exclusion from the group but it only works if the one being shamed wishes to belong. Jesus scorned this shame because he had a quite different set of values and did not belong to the scornful, rebellious world, which was rejecting him.

In Hebrews 2:10 we are told that Jesus was ‘made perfect through suffering’: not meaning that he was imperfect beforehand but rather that in his suffering he achieved a kind of completeness. He came into the world to be our Saviour, the Lamb of God, and on the cross that identity is brought to completion.

The shame of the cross was intended to diminish the victim, instead on the cross Jesus is growing greater. Having suffered death for us, God ‘crowned him with glory and honour.’ (Hebrews 2:9)

*******

For a discussion of the Isenheim altarpiece as a whole, see Laurel Gasque’s article for ArtWay.

Matthias Grünewald: The Isenheim Altarpiece, 1510-1515, 269 x 307 cm.

Matthias Grünewald. Little is known about the artist now known as Matthias Grünewald. His real name may have been Matthias Gothardt; or Neithardt. ‘Grünewald’ was only attributed to him in the 17th century. He was probably born c. 1470-75, and was active as a painter with his own studio from about 1500. It is fairly certain that he was court painter to Albrecht of Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz, who became also Elector of Mainz and from 1518 a Cardinal. Grünewald therefore mostly worked at the Castle of Aschaffenburg, near Frankfurt am Main. Grünewald left the archbishop’s employment in 1526, possibly because of the artist’s sympathies for the Reformation and/or the Peasants’ War. He moved to Frankfurt and then Halle, where he died in August 1528.

Nigel Halliday is a British art historian.

ArtWay Visual Meditation April 10, 2022