Tiessen, Josh - Josh Tiessen

Josh Tiessen: Vanitas + Viriditas (2023)

“Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” ––T.S. Eliot

Tiessen is an international award-winning artist based in Canada, best known for his hyper-surreal and uniquely shaped oil paintings. His pieces often delve into the interaction between the natural world and humanity, drawing on his studies in philosophy and theology. Continuing on that, Vanitas and Viriditas is an exploration of two divergent perspectives on wisdom and how we might flourish in a modern society filled with facts but mired in confusion.

Tiessen’s Vanitas paintings include a figure named Qohelet (Hebrew for “Teacher”). Inspired by the Jewish wisdom book of Ecclesiastes, these works represent the vanity of humans striving for power, wealth, and knowledge, often at the expense of the earth. The art historical vanitas genre, popularized by 17th-century Dutch still life painters, is based on the refrain in Ecclesiastes, “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity.” These images often included motifs such as skulls, moths, and ephemera to remind viewers of the temporality of life and the inevitability of death. Similarly in Tiessen’s works, Qohelet seeks to deconstruct all the ways in which we find meaning and purpose in life that inescapably let us down. He chases after modern idols of science, technology, material consumption, and pleasure, ultimately finding them wanting. Is it all just smoke and mirrors? Is there wisdom in being at peace with the endless paradoxes, or is it cause for despair? The philosophy behind the Vanitas paintings is visually symbolized through an achromatic color palette, Japanese Zen rock gardens, and barren nihilistic landscapes.

The Viriditas paintings are built around a figure named Sophia (Greek for “wisdom”), inspired by the female personification of wisdom from the book of Proverbs. These works espouse virtues such as simplicity, humility, wonder, and awe, which are vital for cultivating ecological wisdom. The 12th-century nature mystic Hildegard of Bingen informed the character development of Sophia, from whom the Latin expression viriditas (translated as “holy greening”) originates. Sophia lives in a harmonious relationship with the natural world, attuning herself to the seasonal rhythms of nature. The vernal color palette in these paintings is bright and cheery—emerald, sienna, yellow, and amethyst, accompanied by Celtic and Gothic Revival aesthetics.

Both Qohelet and Sophia are complemented by animal companions. Qohelet is disenchanted with the natural world and ambivalent toward his fellow creatures since ‘there is nothing new under the sun’. Sophia seeks to learn from the symphony of creation, heeding the advice of the ancient sage named Job:

“But ask the animals, and they will teach you,

the birds of the air, and they will tell you;

ask the plants of the earth, and they will teach you,

and the fish of the sea will declare to you.

Who among all these does not know

that the hand of the Lord has done this?

In his hand is the life of every living thing

and the breath of every human being.”

For Qohelet, wisdom is pursued with “fear and trembling,” accepting the sobering truth that everything in this world is fleeting. For Sophia, the path to wisdom is re-enchantment with the earth and its Creator, manifested in embodied skillful living. The original meaning of the word philosophy –– “love of wisdom” is thereby restored. Flourishing can occur when we align ourselves with the wise grain of the universe.

Sophia Oil on Braced Baltic Birch, 24” x 24” x 2”

In the biblical book of Proverbs, we find four poems dedicated to Lady Wisdom. My interest was piqued when I read in chapter eight that this mysterious figure was the artisan at the Creator’s side, personifying the wise blueprint by which the cosmos was created. We often think of wisdom as head knowledge, but in Jewish wisdom literature it is better understood as practical knowledge, extending even to botany and music. [i]

The 12th century Benedictine abbess and mystic Hildegard of Bingen lived out this embodied wisdom. With a deep respect for the Creator and creation, she was the first to study scientific natural history in Germany. [ii] Like the female artisan of Proverbs delighting in creation, Hildegard loved music and pioneered the first musical, allowing nuns under her care to perform moral plays, even letting down their hair and wearing colourful dresses.

I drew these strands of inspiration into my new muse, Sophíā (Greek for wisdom). Here she is accompanied by a Marvelous Spatuletail. This endangered hummingbird, which only lives in the Andean forest of northern Peru, dons costume-like iridescent plumage and extravagant long tail feathers tipped with purple discs. The American Bird Conservancy has partnered with local Peruvians to create the Huembo Reserve to protect this unique species.

In our modern technocratic society, both religious and secular people are prone to an “excarnate” existence, living life solely in our heads and not in our bodies, leading to an alienation from the physical world all around us. Sadly, children are largely growing up indoors on screens, and are not outside experiencing nature with their five senses––developing Nature-Deficit Disorder, as chronicled in Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods.

Throughout my painting series Vanitas and Viriditas, Sophia’s adventures illustrate that now more than ever we must embody divine wisdom in our relations with one another and the earth.

[i] 1 Kings 4:31-34

[ii] Hildegard of Bingen, Physica and Causae et Curae.

All Creatures Lament Oil on Braced Baltic Birch, 26” x 26” x 2”

“We shall awaken from our dullness and rise vigorously toward justice. If we fall in love with creation deeper and deeper, we will respond to its endangerment with passion.” –Hildegard of Bingen [i]

Physiologus, a 2nd-century monastic text, was a predecessor to medieval bestiaries extolling the moral symbolism of real and imagined creatures, accompanied by lavish illustrations. One of the legendary stories is of a mother pelican who pierces her breast to feed her young, a phenomena believed to take place during seasons of extreme drought. This visceral image was applied to Christ’s self-sacrifice on the cross—shedding his blood to make atonement for the sins of humanity. In the Gospel books of the Bible, Christ likens himself to a mother hen: “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you, how often I have longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, and you were not willing.” [ii] Over the centuries many cathedrals adopted the symbol of the mother pelican and her chicks in the form of colourful stained-glass windows.

Drawing on this theological symbol, my painting depicts a mother pelican’s strident attempt to rise from the oily muck to save her chicks. I had in mind the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on April 20, 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico. This explosion of a rig managed by oil company BP was the largest marine oil spill in history, affecting Brown Pelicans in Louisiana, as well as White Pelicans many kilometers inland. In addition to oil spills, the ecological disaster of ocean plastics proliferates. Fishing nets are the worst perpetrators, and hooks that get lodged into wildlife. By 2050, 90% of seabirds will have plastic in their stomachs. [iii] Recently a train derailment in Ohio unleashed toxic chemicals like vinyl chloride into the air and waterways, resulting in nearly 45,000 animal deaths (primarily fish) and affecting the health of local communities, one of the worst catastrophes in American history. These environmental disasters manifest the proverb, “Whoever sows injustice reaps calamity, and the rod they wield in fury will be broken.” [iv]

When I read the words of Hildegard of Bingen (above) I am reminded that my love for the natural world must also involve a response to its endangerment. “All Creatures Lament” is meant to be an unpleasant and sobering work that spurs us on to action. Looking into the face of an innocent suffering creature, we also look into the face of Christ, remembering that we are called like he was to stand with the oppressed and marginalized, no matter the species.

[i] Hildegard of Bingen, De Operatione Dei, 66.

[ii] Matthew 23:37

[iii] All Creatures Podcast, Episode 291.

[iv] Proverbs 22:8

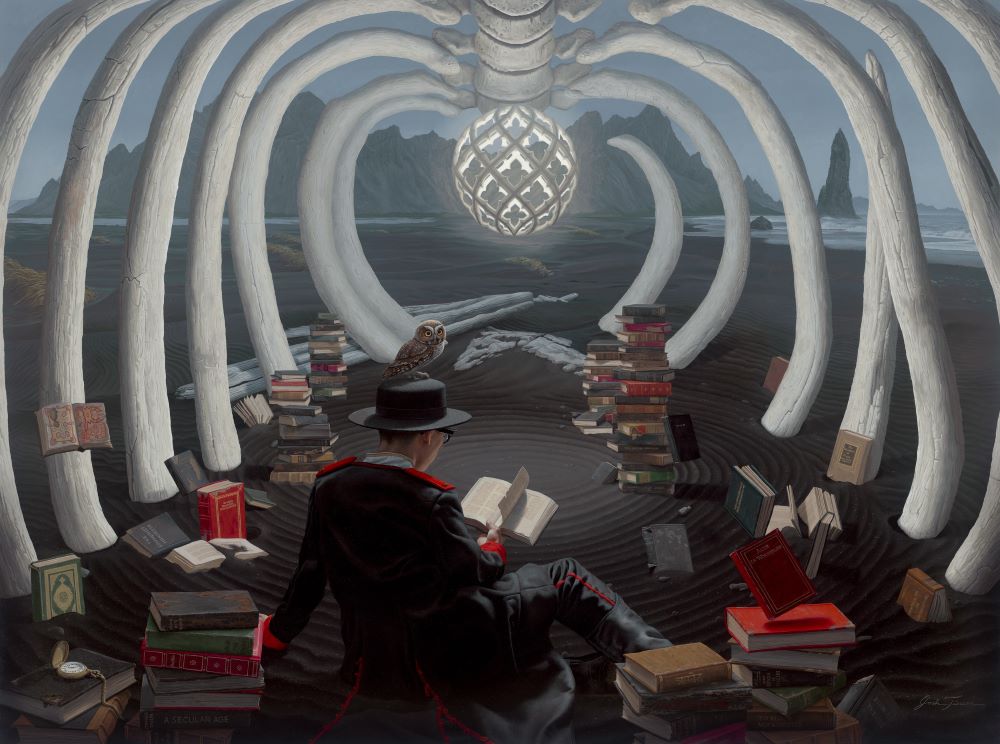

Swallowed by Knowledge Oil on Braced Baltic Birch, 30” x 40” x 2”

After a life pursuing knowledge, Qohelet concludes: "Of making many books there is no end, and much study wearies the body." [i]

The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard criticized the work of the German metaphysician Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who believed humans could arrive at objective truth through a rational systematic approach to knowledge. [ii] Instead, Kierkegaard emphasized that we are temporal and finite beings, and the best we can do is with “fear and trembling” take a leap of faith.

The barren Icelandic black sand landscape in my painting is metaphorical for the epistemic nihilism Qohelet experiences in his quest for understanding. Certainly there is merit in studying broadly, and logically evaluating a plethora of truth claims. Being well-read is part of a rich and full life. Fine novels ignite our imaginations, and books about history, science, religion, and politics, expand our horizons.

However, no one can possibly read every book written and assert omniscience (all-knowing). Contrary to what our 'smart' phones would have us believe, we are sadly no more the wiser! We are experiencing what Charles Taylor termed the “Nova Effect,” a rapidly increasing array of life philosophies that are now on offer. [ii] Qohelet discovers that what we really need is not additional information, but true wisdom. Some of the most diabolical eugenicists and dictators were (and are) well-educated individuals. When we seek to find our entire purpose and meaning through the acquisition of knowledge we self-delude, rejecting a relationship with our omniscient Creator––the Light that can help us discern true wisdom from the wisdom of this age.

Viewers of this painting may notice the allusion to the biblical story of Jonah and the Whale, evidenced in Qohelet's place within the skeletal rib cage of a massive Sperm Whale. These intelligent mammals have brains six times the size of humans yet, like us, they suffer the same fate of death: "the dust returns to the ground it came from." [iv]

The Elf Owl perched atop Qohelet's head recalls Celtic tales of saints such as St. Kevin of Glendalough (498-618). Living in complete solitude in the wilderness, he was in such earnest contemplation and prayer that a blackbird built a nest in his open hands. [v] The insertion of the curious owl evokes the irony and humour indicative of when we get 'lost in a book' oblivious to the world around us... as Qohelet is often prone to doing!

[i] Ecclesiastes 12:12

[ii] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, 423.

[ii] John Caputo, How to Read Kierkegaard. 12-13, 27.

[iii] Ecclesiastes 12:7

[iv] Tracy Balzer, Thin Places. 114.

*******

Josh Tiessen was born in 1995 in Moscow, Russia. He is an international award-winning contemporary artist based near Toronto, Canada. Tiessen is best known for his hyper-surreal shaped oil paintings, which take up to 1700 hours to complete, and reflect the interaction between the natural world and human-made structures, drawing upon his studies in philosophy, theology, and environmentalism.