The ever popular "Sweet Caroline" by Neil Diamond speaks of

“Hands

Touchin' hands

Reachin' out

Touching me, touchin' you”

This is the ideal scenario for human relationships, hands reaching out one to the other, whether in friendship, as when hands are shaken or hugs exchanged, or in love, as the bodies of lovers are entwined.

This is also a familiar trope in the visual arts, most famously, of course, in Michelangelo’s The Creation of Man where God's right arm is outstretched to impart the creative spark of life from his own extended finger into that of Adam. The left arm of Adam is extended in a pose mirroring that of God the Father and the connection between the two is a reminder that God said, "Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness" (Genesis 1:26).

However, there is also significance to be found in the fact that their two index fingers are separated by a gap of about 3⁄4 inch or 1.9 cm, leading some commentators to suggest that this gap represents the unattainability of divine perfection by human beings. The gap between the fingers of those reaching out to one another is also a reminder that the ideal is not always what characterises our relationships as human beings. Hands can reach toward another for reasons other than love and friendship, while circumstances or other emotions may mean that the hands of those reaching out in love or friendship do not actually connect.

This understanding of the visual gap between God and humanity in Michelangelo’s image has been replicated and revised elsewhere within the visual arts; one example being ‘The Descent from the Cross’ by David Folley at St Andrew’s Wickford. Alan Thompson writes of a detail within this image: “From the bottom of the painting is an outstretched arm, which just fails to touch Christ's hand, because the hand is withdrawn. This is intended to signify man's desire, through science, to explain the laws of the universe and so become almighty. He is almost there but cannot touch. There is a visual tension between God and man.”

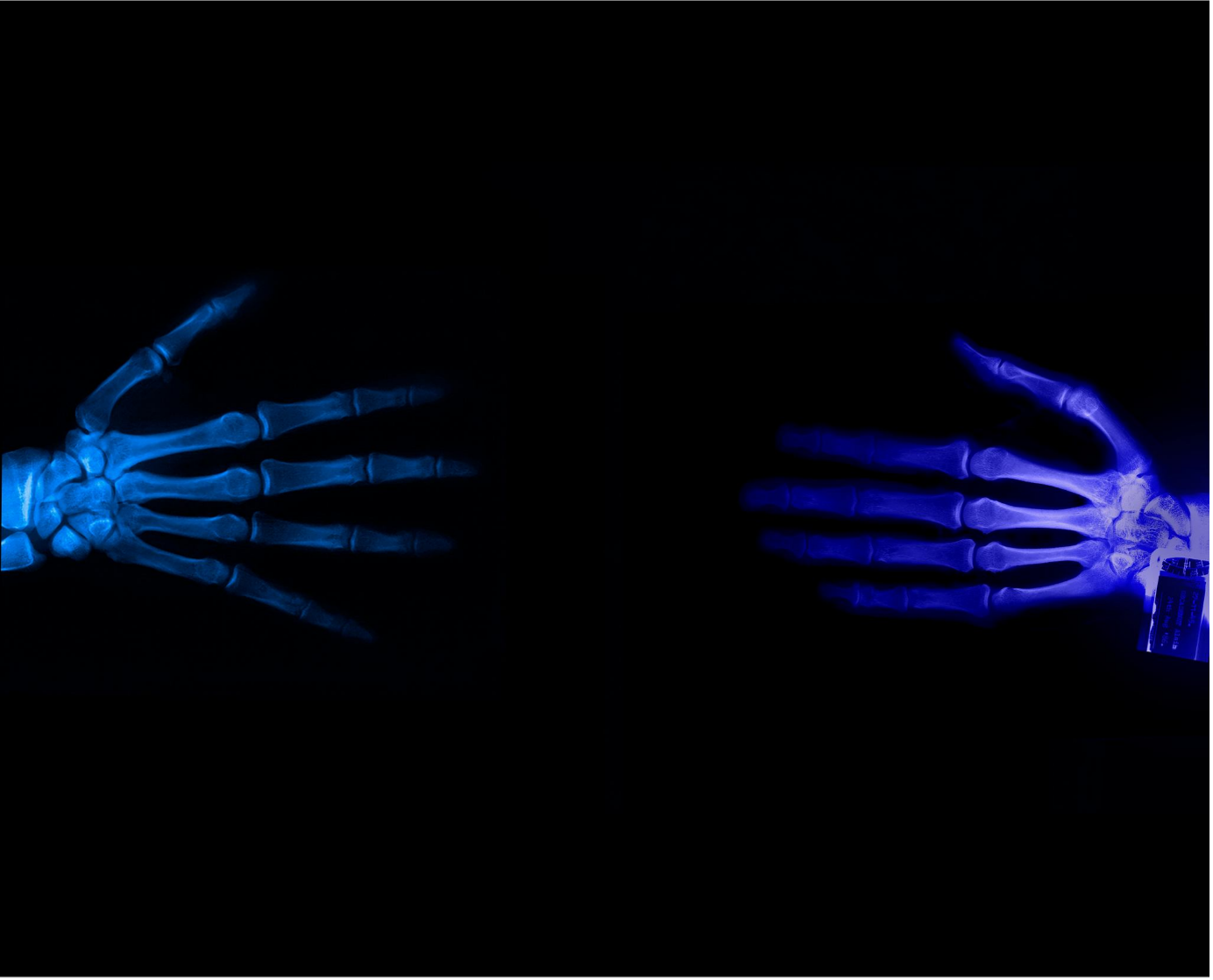

Alexander de Cadenet’s image, which combines X-rays of his hand and that of his father, sits within this tradition of images but expands it in new directions. De Cadenet experienced a somewhat conflicted relationship with his father, the racing driver and TV presenter, Alain de Cadenet, and the space between their hands may symbolise the ways in which they failed to connect.

Despite that painful reality, there is also a continuing bond (whether resisted or not) between parent and child that derives from the link between creator and created. This image of father and son continuing to reach out toward one another explores the reality and complexity of that bond, which mirrors that of God the creating Father reaching out to Adam who, as the first man, represents the son.

De Cadenet is fascinated by the potential that X-ray images possess to reveal and/or mask the nature of the person that has passed. He has explained that his skull portrait series uses manipulated X-rays of skulls "to explore the deeper identity of the subject even beyond their mortality." He is particularly engaged by the paradox of the skull portraits, that while they capture the intrinsic essence of their subject, they simultaneously anonymise them. Speaking of the series, he has said:

It’s fascinating to me that as an artist I can contribute in a small way to the ongoing legacy of the subjects, this is for me one of the more meaningful purposes of portraiture in that there is some transcendence from the finality and depressing nihilism of death. I also enjoy the paradox of presenting “who the subject really is inside” yet this also can be a mask, as you cannot recognise the person by looking at their skull. Ultimately all my art is about exploring what is giving my life meaning and, on this subject, a contemplation of mortality is a chance for deeper spiritual contemplation and questioning. The skull portraits can even hint at the more meta-physical dimension, the soul. What happens to the soul after death? Can the living still impact the souls of the departed? Maybe art can have some part to play in these eternal questions.

There is a significant synergy between this image and the skull portraits going beyond the shared use of X-rays as the following statement from De Cadenet makes clear:

The skull portraits began in 1994 as a way to share my authentic voice with the world in a meaningful way. Over time, they have evolved into an exploration of identity—how it is created, maintained, and transformed—mirroring my own journey of self-discovery. These works not only honour the individuality of their subjects but also propose that identity transcends death. Through the medium of art, I suggest that something of a subject’s essence can endure, and perhaps even evolve, beyond physical existence. This impulse—to leave a mark on the world—echoes humanity’s oldest instincts, seen in the primal cave paintings of hands, where our ancestors expressed their raw desire to affirm their presence and give meaning to their finite lives.

The personal nature of this image and the reality that the live son is reaching out to the dead father (reversing somewhat the order found in “The Creation of Man,” where the creative spark animates the dust of the earth to give life to Adam) leads towards another iconic Christian image that further extends the depth of our reflection.

“The Harrowing of Hell” is an icon depicting Jesus’ descent into Hell, after his crucifixion and before his resurrection, to free the souls of the damned. In this image the hand of God the Son reaches out to the hands of those who have died in order to bring rescue and salvation to them. In this image, there is no gap between the fingers of God and humanity instead Jesus firmly grasps the hand of each damned soul in order to pull them from the depth of their torment.

This is an image which has become deeply meaningful to de Cadenet since his father’s death, and one which has inspired this work that combines his hand with that of his father. The story and icon of “The Harrowing of Hell” suggests that it is possible to touch and change, in the afterlife, the lives of those that have died. The reaching towards one another seen in this image suggests that possibility. It is a possibility that informs the practice of praying for the souls of the departed as also of Catholic ideas regarding limbo, the border zone between heaven and hell.

At the end of 1 Corinthians 13, his famous passage on the nature of love, St Paul writes that faith, hope and love abide or remain. The word used for “remain” implies that we can take something with us when we die; that all our acts of faith, hope and love from this life continue and are perfected in our future life. This means that funerals are important times for us to reflect on our own lives: Are we modelling our life on what we know of Jesus? Are our lives characterised by acts that are full of faith, hope and love? If not, then we will enter eternity with very little. But what a joy there is when someone can take much that was of love into their future life together with God.

De Cadenet’s “Skull Portraits” and this image function as memento mori prompting reflection on mortality and its significance in relation to the big questions of life; questions of being, meaning, and belonging. De Cadenet says:

Mostly it's the idea of impact post mortem and how we can impact the souls of the departed. Also, how art can contribute to the ongoing legacy and story of their life well after their passing. Someone's identity is also about how history reads them and art can impact that. So, what's happening in the terrestrial world is seemingly happening in the spiritual meta-physical realm. Art is the bridge between these worlds.

He concludes with a quote from Cosimo de Medici, one the greatest art patrons ever to have lived, which acknowledges this role of art: "All those things [works of art] have given me the greatest satisfaction and contentment because they are not only for the honour of God but are likewise for my own remembrance."

De Cadenet’s artworks reflect the evolution of his own consciousness and the sorts of statements he wants to share in the world:

Being an artist is about having a voice in the world, a pure and authentic voice in a challenging world. It is a way of sharing personal insights and encounters with the world, of exploring the mysteries of our existence and our place in the grand scheme. Art is the intersection between the formless dimension and the world of form; it embodies our connection to nature or the intelligence that is responsible for our existences.

This new work extends his evolution in new directions and to new depths of understanding, both personal and spiritual.

%20(1).png)