Interview with Peter Koenig

Interview with Peter Koenig

by Jonathan Evens

Peter Koenig knew from a young age that his vocation was to be a religious artist. He told his Art School Head that was the case and undertook a further course of study at the Visual Arts Academy in Nuremberg to study frescos in particular, but also graffito, fibre-glass and engraving, because he was dissatisfied with the blandness of much contemporary religious art.

Over the course of his lifetime he has read the 73 books of the Bible many times, primarily using the Jerusalem Study Bible to explore cross references in the story of salvation. His paintings are based on the imagistic interwoven connections that Koenig has explored through his regular and deep reading of Scripture. His practice demonstrates that the way to avoid blandness in religious art is immersion in Scripture.

Stephen Holmgren has written that Koenig’s paintings are profoundly biblical while not being literal. That seems to me to be the reverse of what Koenig does in his art. Koenig gives us literal representations of the images that Scripture uses to describe salvation. Just as Scripture interweaves these images throughout the drama of the salvation story, so Koenig interweaves them on his canvases. Holmgren rightly notes that thereby Koenig is seeing and showing ‘the mystical connection between the Old Testament and the New.’ The result is somewhat surreal, precisely because the scriptural imagery that Koenig uses is surreal.

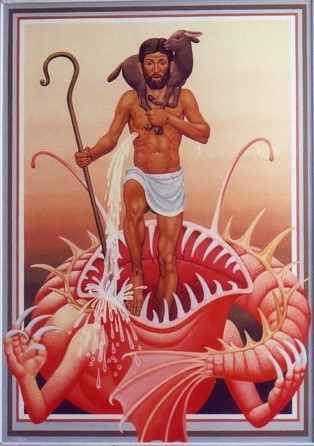

Christ the Bridegroom, the Resurrection and the new man, all the teaching and dramatic actions of Christ especially the Parables; these are among the images Koenig has used for their inherent drama. Images such as Christ weeping in Entry into Jerusalem or The Good Shepherd and Leviathan, with the Risen Lord stepping out of the mouth of a sea monster, are powerfully compelling, although unusual depictions of their subjects. Both utilise lesser known biblical imagery and understandings of the texts that are psychologically astute. Peter notes, for example, that leviathan is a monster that swallows up its victim like death and links this to the line in Psalm 30, ‘You have brought up my soul from Sheol.’

Koenig’s faith was formed in pre-Vatican II days as he makes crystal clear in this interview, yet his art reveals complex depths and an openness to interpretation because his deeply held beliefs make the imagery of Scripture the foundation of his work. As a result, the complexity and drama of Scripture is front and centre in his work.

Koenig has said that the goal of his life has been to make a richer Christian-Catholic art by painting the drama, romance and poetry of the sacred book. In this interview we explore the way in which he has approached this task.

JE: You have said that ‘One must first have a sense of the mysterious, the holy, before one sets out to be a religious artist.’ I want to explore with you the two parts of that statement, beginning with the understanding that you specifically set out to be a religious artist having decided, as a teenager, to paint religious subjects. Can you explain more about your thinking and motivations at that time? How did a sense of ‘the mysterious, the holy’ manifest for you then and also now? Are there differences between the two? Why is this sense so important for a religious artist?

PK: I feel somehow that the first question is not merely a personal question. Abraham set out from Ur. He was following the call of God (and how much does that word contain!). We are not born with a language or knowledge of the past, we have to be taught it by word and action. That is what Christian education seeks to do. Holy mystery is learnt by going to the Eucharistic Assembly-Mass. At Mass as a child I was brought there to meet God. So when the priest paid our family a visit I would excitedly cry, ‘God is coming!’

JE: The art school that you attended was staffed by agnostics and was, therefore, not the best place for one, like you, who wanted to produce sacred art. How difficult has it been for you to pursue your vocation as a religious artist in our secular society?

PK: When I went to the High Wycombe Art School (now Amersham), I told the headmaster that I wanted to produce and study religious art. He (an agnostic) said all art is religious. That is both true and false at the same time. The Art School, from a Christian perspective, was disappointing but that is another story. But escaping that place after I had finished the course I could feel free to set my own course.

JE: You describe going to Art School knowing the calling of God on your life - to produce religious art - and you seem to have pressed on towards the realisation of that calling despite misunderstandings or discouragements (particularly when training as an artist). Once you left Art School you could then set your own course and have since consistently created paintings that use the huge diversity of imagery and story with the Bible for your inspiration. You responded to your calling as Abraham did his, yet the letter to the Hebrews tells us that Abraham was among those who died in faith without having received the promises. That doesn't appear to be the case for you, as your calling to create religious art would seem to have been achieved. How do you view the journey of art and faith that you have undertaken and the work that has been made as you have journeyed? What have you learnt about art from your journey and what has the making these artworks taught you?

PK: How do I view my journey of faith and art? What have I learnt from my journey and what has the making of these artworks taught me? Those are very introspective questions. Well, not every style of art is equally suited for the subject or every book of the Bible. I usually remind myself that all art is transient. Indeed, ‘all flesh is grass and like the wild flower it fades, the grass withers, the flowers fade but the Word of the Lord is forever!’

JE: Carl G. Jung has been an influence on your work and thinking. How has that influence and the ‘worrying things rumbling about in the dark regions of the soul’ shown itself within your work?

PK: Talking about Carl G. Jung for a moment, I read him before Vatican II. I am one who does not approve of much that followed on from that event – something is being downright silly. But Jung’s influence, such as it was, is revealed in Christ stepping from Leviathan, rescuing a sheep. I believe he writes somewhere of the Hero, or the self, needing to face the abyss to overcome it. But it is a long time since I read his Collected Works.

JE: Pope Francis has implored artists to ‘make the deep beauty of God’s love visible’ and to help people ‘discover the beauty of being loved by God and bear witness to it in attention shown to others, especially those who are excluded, wounded and rejected in our societies.’ Beauty, he has said, is a much better path to understanding than technology and he has, therefore, urged artists to create and safeguard ‘an oasis of beauty,’ especially ‘in our cities, which are too often filled with cement and lacking soul.’ The letter that Pope John Paul II wrote to artists in 1999 was for those who are passionately dedicated to the search for new ‘epiphanies’ of beauty so that through their creative work as artists they may offer these as gifts to the world. What is there in the statements that the Church has made about art and artists that resonates with your own understanding of your calling?

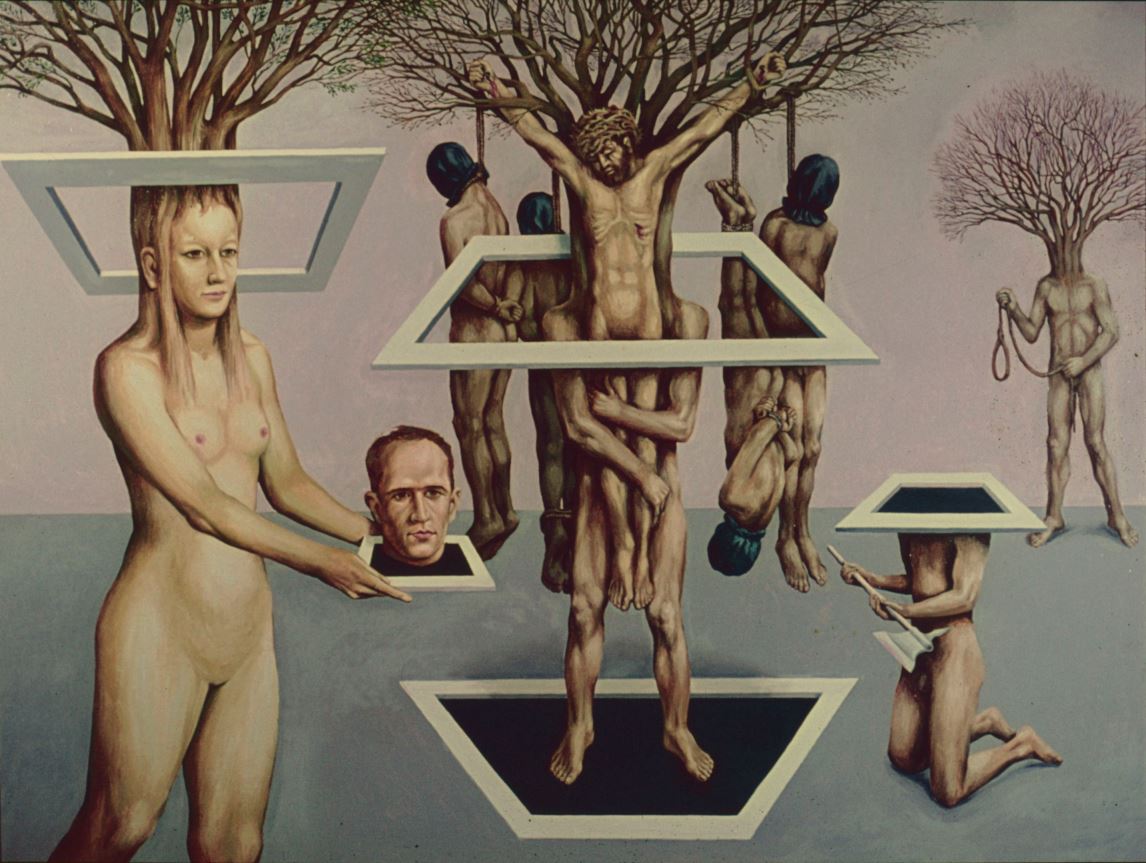

PK: You gave a nice quotation from Pope John-Paul II, but Pope Francis is a quixotic individual. He seems more interested in Globalism (who will sit at the top of that pyramid?) than in his flock. Would he really lay down his life for the sheep? What would St Peter and St Paul make of his party in the Vatican Gardens with the ‘Pachamama Idol’? How about his, ‘God willed all religions’? What does that mean, apart from something trite? Rome, the ‘city of martyrs’? Would he have been one? As for martyrs, I have of course painted martyrs; namely St Ignatius of Antioch and Blessed Franz Jaegerstaetter who appears in several paintings. (The Birth Pangs of the World and Wisdom is the Tree of Life)

I associate ‘Wisdom is the tree of life (to him who holds fast to her) [Proverbs 4:13, 18]’ with the following quotes:

‘Oh, this cowardly fear of me! Because of a few jeering words spoken by our neighbours, all our good intentions are thrown overboard.’ (From Franz Jaeggerstetter’s letter to Franz Huber)

‘But Christ too, demands a public confession of our faith, just as the Fuehrer Adolf Hitler, does of his followers.’ (From his article ‘Little Thoughts concerning our past, present and future’)

The lady on the left holding Franz Jaeggerstetter’s head is the tree of Wisdom. In the centre, we see Jesus on the cross, which is a tree and a person carrying the executed, surrounded by hanged men who represent those who were martyred by the Nazis in Poland. Franz was executed by beheading, hence the headless corpse on the right. Then on the right side we have the tree of reckoning, holding the noose.

JE: You have suggested that ‘Catholic Art in England is preoccupied with a devotional range of subjects’ but that ‘there is much more imagery in the Bible’ than is tapped through those devotional subjects. Is your sense that Christian-Catholic art can be richer to do with utilising the breadth of biblical imagery?

PK: In 1966 I acquired one of the first editions of the Jerusalem Study Bible with copious notes (and printer’s errors). Christianity is for want of an inadequate word, Jewish. That Bible has all the cross references of the ‘Story of Salvation’ a man like me could want. What a fascinating collection/ combination of books it is! In the Catholic tradition there are 73 books and I have read them all many times. The story of salvation begins with Abraham and I suppose continues today.

JE: Your work has depth and complexity because you understand and utilise the breadth of imagery within the Scriptures and the linkages between the many books. Understanding the imagery of leviathan and its relevance to Christ's resurrection suggests an engagement with Scripture and an understanding of its themes that is unusual in an age when knowledge of the Scriptures seems diminished, even among the faithful. How can we recover the kind of engagement with Christian education that you enjoyed as a child?

PK: May I start with a sort of question? Is life a ‘Thompson Holiday’ or is it a drama? Well! Now with the Covid bug it seems very much a drama. Reading the Bible, it is all drama with exceptions. You are quite right the Bible is not read for interest, fascination and wonder which may be due to how it is taught. A missionary was having a hard time getting the ‘Word of God’ over to his Hindu audience. So he tried acting and yes, drama. The people said ‘Now we understand what you are saying!’ I could image the story of Jeremiah being performed by school children and getting a good response. Jeremiah confronting his fellow Jerusalemites and being thrown down a well; the city ransacked. You know there are lots of people preaching the Gospel very well but painting has a good supporting role to play. I’m sure some of the images which I painted from the Bible, like the little boy putting his hand in the snake pit, must get some reaction from youngsters.

JE: You have said that the goal of your life has been to make a richer Christian-Catholic art by painting the drama, romance and poetry of the sacred book. Reviewing your work, where do you think you have come closest to achieving this goal?

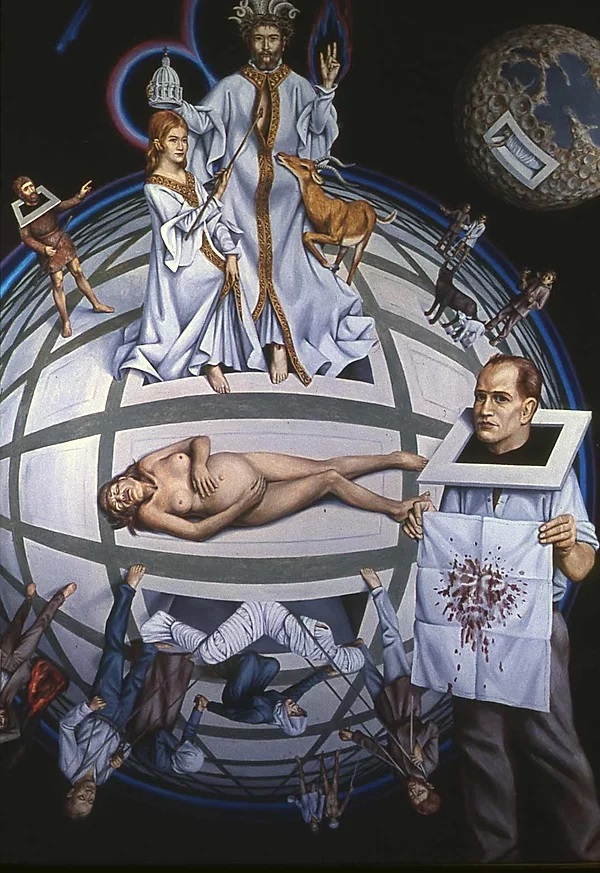

PK: For The Birth Pangs of the World I give this quote: ‘From the Beginning till now the entire creation as we know has been groaning in one great act of giving birth and not only creation but all of us who possess the first fruits of the Spirit... We groan inwardly as we wait for our bodies to be set free.’ (Romans 8:22) In this painting we have the drama of Christ’s victory over death, to which people like John the Papist and Franz Jaeggerstetter give witness. The birth pangs are literally represented by the pregnant woman in the centre and the whole church participates in and experiences this passage from death to life in Christ. We are especially aware of this in our time when all churches are undergoing the pangs of renewal, while striving for unity. All the squares on the earth that Jesus sits on are tombstones of past generations. And you have further reminders of death with the burial at the bottom, and the Vietnamese monk burning himself alive in the corner in protest at the Vietnam War. The moon could potentially be a place where people will live and eventually be buried there. You can also see the wolf lying down with the lamb, and behind Francis of Assisi. In the centre you have Jesus crowned in victory, with Mary at one side, embodying the church, and the deer thirsting for water from Psalms.

JE: Your paintings are displayed periodically within the Parish of St. Edward’s (Roman Catholic Churches serving the communities of Kettering, Burton Latimer, Desborough and Rothwell). Permanent works appear on the chancel in St. Edward’s and St. Bernadette’s churches. Can you tell us more about opportunities to see your work in a church context and commissions you have undertaken?

PK: The originals? Where are they? St Edward’s Church has a hall where many paintings are on a sort of permanent display. Many of the paintings are in private hands, three in Germany, four in Austria, and Belgium must have a dozen or so. There is even one in Japan and one in Canada. I have a selection, mainly of earlier work, but a cross section of others. I have quite a number I have never publicly exhibited - except for now on the Internet.

****

Images:

1. The Good Shepherd and Leviathan

2. Peter Koenig at work on Jeremiah down the Well, a painting begun during the course of this interview (copyright Gaby Koenig)

3. Wisdom is the Tree of Life

4. Boy and Snake

5. The Birth Pangs of the World

Peter Koenig’s parents left Austria just before the German take-over and he was born in London in 1939. He was educated at St Benedict’s School, Ealing Abbey, London, where he later taught for 25 years. He gained his Diploma in Arts and Design in High Wycombe and his teaching Diploma in Leeds. In 1967 Peter Koenig went to the Visual Arts Academy in Nuremberg to study frescos in particular but also graffito, fibreglass and engraving. He made full use of such techniques and filmmaking with his pupils, who include Andrew Serkis of Lord of the Rings, and with the drama department producing theatrical masks and stage sets. His paintings can be seen in various churches of Northampton diocese, as well as wall hangings designed by him and sewn by parishioners. He is a life-long member of the Society of Catholic Artists in London and was president from 1973-1980. https://www.pwkoenig.co.uk/ http://www.stedwardskettering.org.uk/christian-art-koenig/

Peter Koenig is a life-long member of the Society of Catholic Artists in London and was its president from 1973-1980. The 90-years-anniversary exhibition for the Society of Catholic Artists can be viewed here.

Revd Jonathan Evens is Associate Vicar for HeartEdge at St Martin-in-the-Fields. Through HeartEdge, a network of churches, he encourages congregations to engage with culture, compassion and commerce. He is co-author of ‘The Secret Chord,’ an impassioned study of the role of music in cultural life written through the prism of Christian belief. He writes regularly on the Arts for a range of publications and blogs at https://joninbetween.blogspot.com/.