There is a vulnerability to flesh – that which can be pierced and torn can be emptied. The body that suffers and breaks is a central concern within the work of Belgian artist Berlinde de Bruyckere, whose sculptures and drawings attend to the fragility of flesh. Speaking of her practice, De Bruyckere reflects, ‘I want to show how helpless a body can be.’ For De Bruyckere, the body’s helplessness is not fearful but is rich in potential for beauty and contemplation.[1] This potential is given shape in De Bruyckere’s 2007 Piëta works. While De Bruyckere’s is known predominantly for sculpture, it was her pencil and watercolour work on paper, Piëta (2007) at the Foundling Museum’s 2024 exhibition The Mother and the Weaver that struck me with its contemplation of the helpless body.

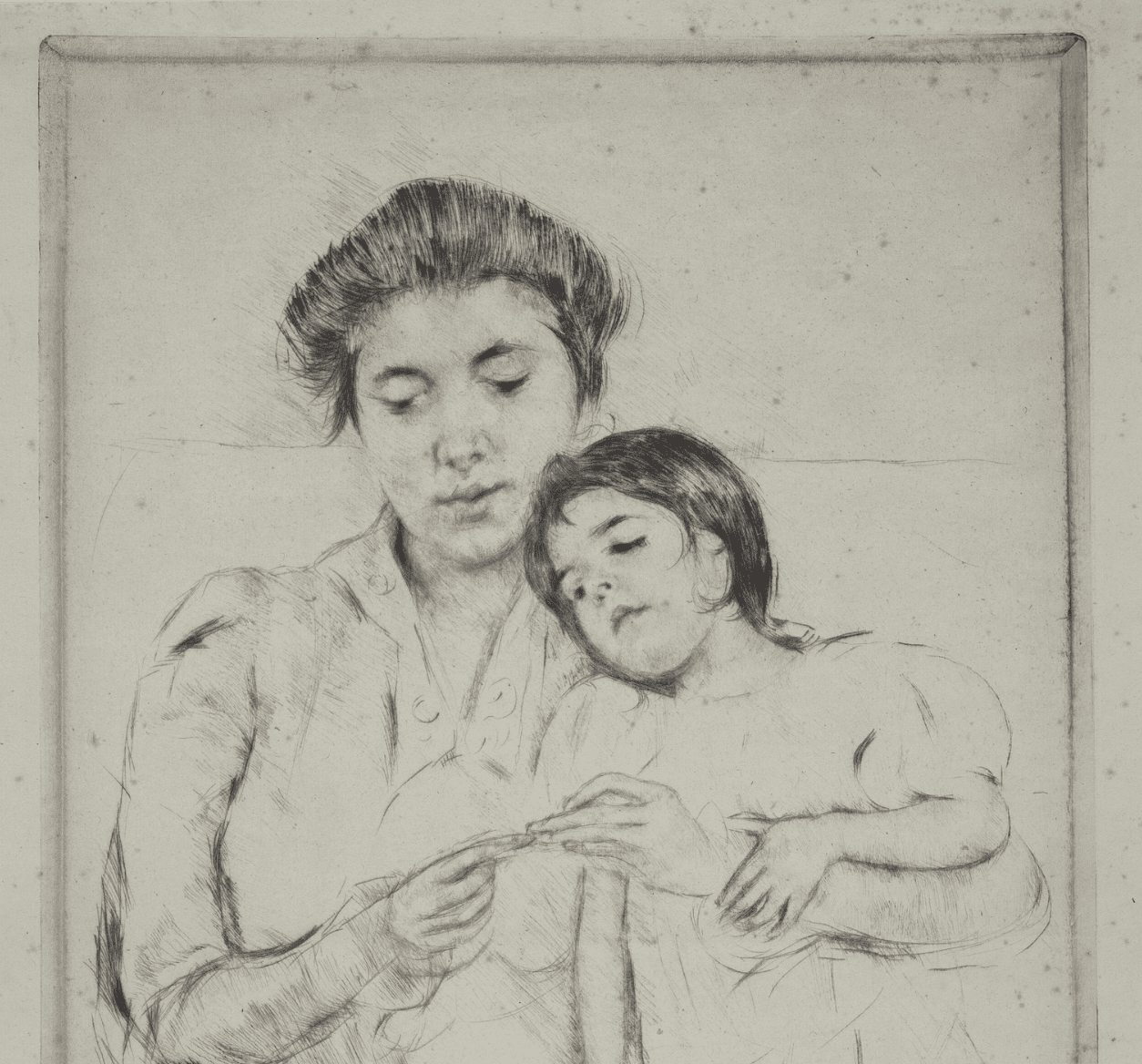

The abstracted figure is alone, shrouded by a graphite darkness that lifts the gentle pink flesh tones of the centred body. Following the contours of the figure that dominates the frame, the number of elongated limbs begins to suggest not one but two bodies. The two bodies disappear into one another, with few lines distinguishing their flesh and describing them as separate. It is the oneness of these figures and their appearance of sharing a single flesh that reflects De Bruyckere’s sculptural sensibilities. Such a quality perhaps references not only De Bruyckere’s own sculpture works of the same name, but also the Old European Masters whose visual language the artist often draws from.

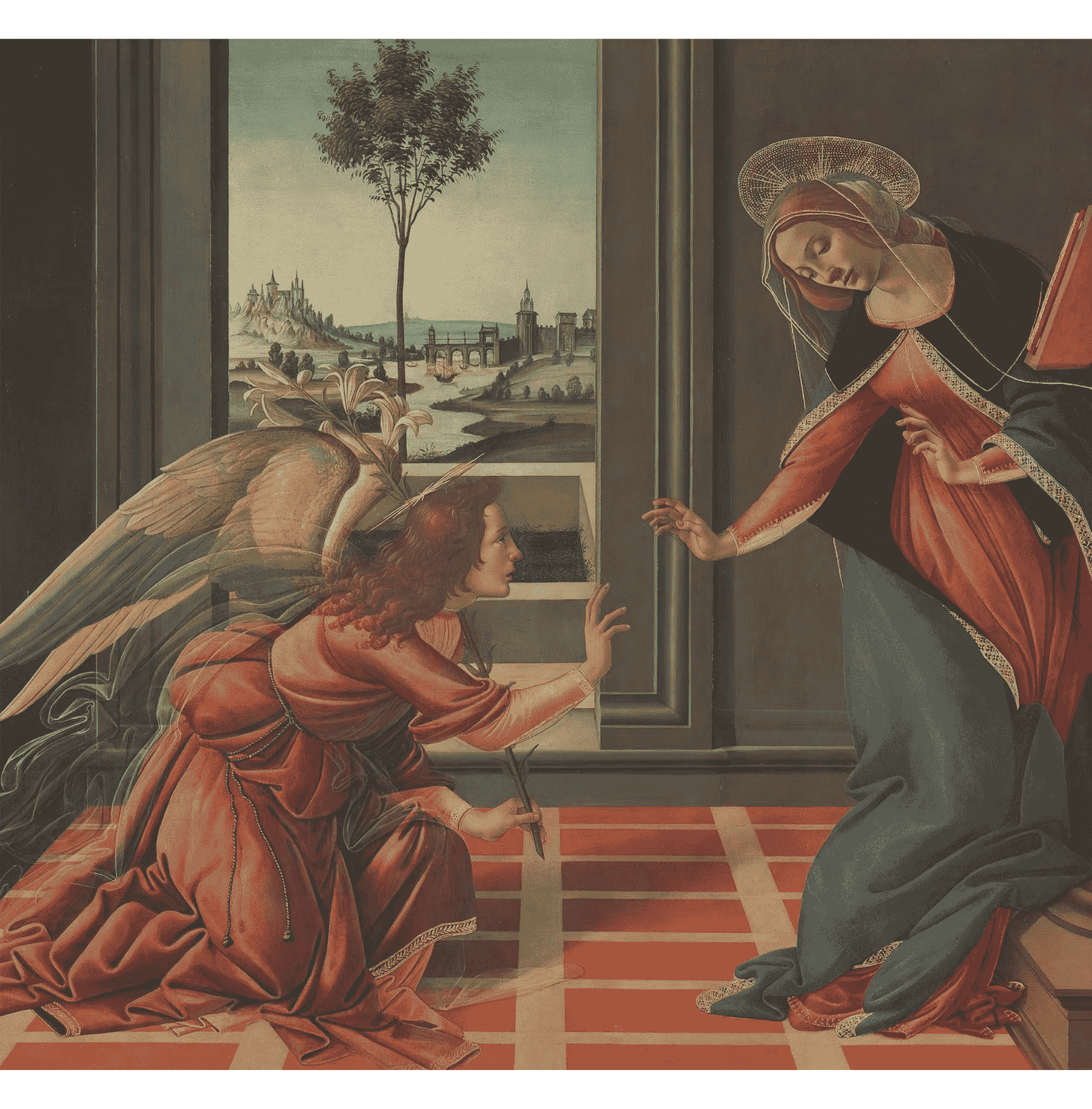

By adopting the title Piëta, translated pity, the work echoes a broader Christian iconographic tradition of depicting the Virgin Mary holding the body of the slain Christ. The title, and its reference to this tradition, clarifies the suspicion that these are indeed two figures. The most famous work depicting the Piëta, is Michelangelo’s 1498 sculpture in St Peter’s Basilica utilising Carrara marble to depict the figure of the crucified Christ lying upon the knees of His mother – the folds of her fabric acting as a podium on which His body rests. Michelangelo’s portrayal of the Pietà is distinct from other European artists in his success at unifying the figures of Christ and the Virgin Mary, overcoming the aesthetic awkwardness of balancing a grown man on the lap of a woman.[2] It is the balanced unity of these two figures emerging from the marble that appears to be echoed in De Bruyckere’s piece.

In De Bruyckere’s Piëta, two bodies melt together into one flesh; the Mary figure is hunched over the Christ – whose body lies in a position of empty surrender. At first it seems that Mary bears the Christ’s weight, as is in traditional Pietà’s. But here, the Mary figure is not grounded – but rooted in the flesh of the Christ. It is unclear who is bearing the weight of this embrace. The piece speaks of a dependency between a mother and her child, a resonance deepened by its setting in the Foundling Museum. There is a universality to the scene, the heavy grief of any mother who has lost her child. Yet the work also pulses with the particularities of its theological motif.

Mary’s grief at the foot of the cross is only briefly noted in Scripture. In John’s Gospel Jesus tasks his beloved disciple with the care of his mother in His absence – a moment emphasising a tenderness between Christ and his mother (John 19: 25-27). Later, we see Mary along with the other women attending Jesus, following him from afar (Matt 27: 55-56; Mark 15: 40-41; Luke 23:49). But in the tradition of the Pietà, artists have given visual form to an imagined scene: the mourning mother cradling her dead son. She who once gave her flesh to bring forth the humanity of the Son of God now grieves that same flesh as it is torn and emptied. The work, as with much of De Bruyckere, is difficult to look at. Her distortion of human flesh to the point of abjection, and her evocation of the suffering body can cause us to resist a prolonged contemplation of her work – we want to look away. However, the beauty of the Piëta is in its invitation to dwell carefully on the horror of Christ’s helpless and broken body. It calls us to resist the urge to move too quickly towards our anticipation of his resurrected body. To see Christ’s incarnate body in its vulnerability, pierced, torn, and emptied, is to be confronted with the reality of the gospel. It is only by contemplating the ugliness and abjection of Christ's mutilated body as he endures the full extent of his passion that we can begin to appreciate the full beauty and redemptive potential of the incarnation.

NOTES

[1] See https://www.hauserwirth.com/artists/2782-berlinde-de-bruyckere/

[2] Peter Murray and Linda Murray, The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 323.

*********

Berlinde De Bruyckere, Pietä, 2007, Pencil and watercolour on paper, 61 x 48 cm / 24 x 18 7/8 in.

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Ghent, b. 1964) is a Belgian artist who creates sculptures that reveal the human body and human life in all its frailty. Her installations of equine and human bodies evoke feelings of terror, but also of love and consolation. The work is both emotionally immersive and provocative, regularly creating controversy. De Brucykere’s bitter-sweet images unite pain and suffering with a strong aesthetic appeal. Her Cripplewood presentation attracted great public attention at the 55th Venice Biennale. The SMAK Museum in Ghent and the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague held a major retrospective of her work in 2015.

Rebecca Nunes is UCCF’s Arts Network Coordinator. She has a background in Fine Art and History of Art, and works in Cardiff alongside UCCF's Arts Network to equip and resource creative students. In this role she supports those studying within the arts to consider how to best engage with the challenges and opportunities of the arts, how to contribute well as creative Christians to the dynamic cultural landscape, and how to reach fellow creatives with the life altering message of the Gospel.

%20(1).png)