When reading the domestic account in Luke, women in Latin America may find themselves identifying less with Mary and more with Martha. In South America, offering hospitality extends beyond simply providing a place at the table—it often involves an aesthetic dimension that is woven into the experience. Whether going the extra mile with elaborate cooking or organizing an artistic performance for guests, the time, effort, and creative energy poured into hosting reflect a cultural trait in which women typically bear the load.

The weariness of constant service leads to an unspoken but deeply felt question: "Lord, don't you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!" (Luke 10:40). Yet many women–socially conditioned not to complain, especially to their husbands, brothers, or fathers–suppress this cry. Instead, they continue serving while a quiet resentment grows, passed down silently from generation to generation.

Sociologists and historians continue to examine the strong moral framework that shapes Latin American societies. A historical nature-grace dichotomy, rooted in the colonial legacy of medieval Roman Catholic thought, undergirds this framework. This theological and philosophical distinction separates the "natural" realm of everyday life, culture, and social structures from the "supernatural" realm of divine grace, creating a sharp divide between the secular and the sacred.

In Chile, this dichotomy reinforces a compartmentalized view of life, where moral and religious obligations are assigned to a higher spiritual sphere, while material and cultural dimensions are seen as inferior. Among evangelical Christians in Chile, the ongoing tension between the secular and the sacred deepens the divide between church and society. Rather than drawing on a theology of redemptive love, evangelicals often relate to society through a framework of moral obligation. As a result, those outside the evangelical community are frequently perceived as "the other," the sinner, the unrighteous, who must repent to align with the community's moral norms.

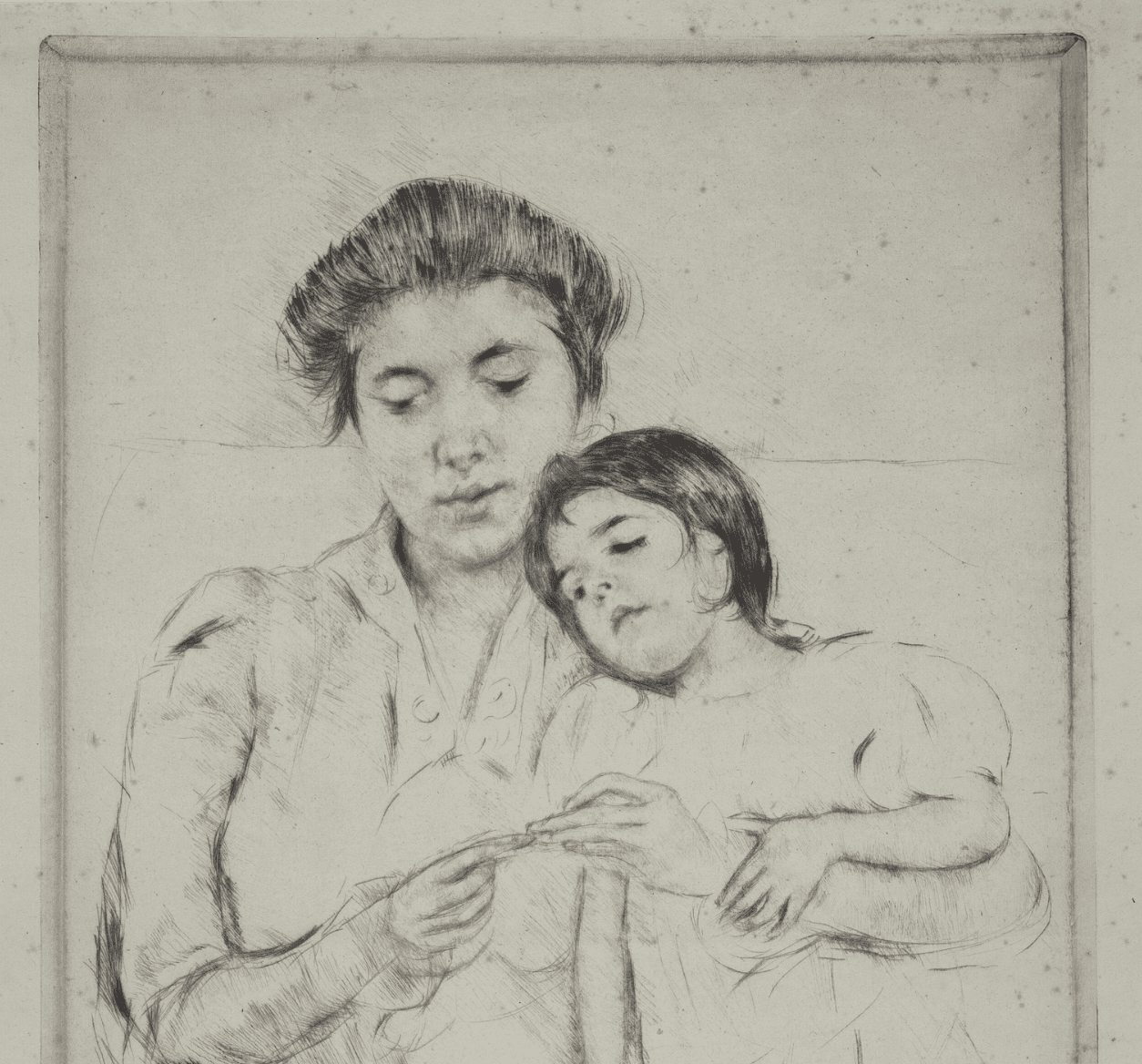

The deaf Chilean urban artist Juan Pablo Gatica–known as JP–beautifully captures in the graffiti above what my doctoral research on urban evangelicalism in Chile revealed: a profound moral dichotomy within otherwise hospitable and beautiful encounters. Behind many acts of love and hospitality lies a tension between beauty and burden–a deep moral layer that reflects obligation more than freedom. Kindness is often extended not purely from generosity but from a powerful cultural expectation to do so. As a Chilean, JP is likely aware of the social pressure placed on women to continue serving without complaint, regardless of how tired or unwell they may be. His art does more than reveal this tension–it invites us to recognize and reflect on it. In this work, Garden of Offerings, he composes a South American representation with striking contrasts: light and shadow, apples and chains, roses and thorns. Through everyday scenes—such as sharing food—he reconstructs the mixed European and indigenous mestizo heritage he knows intimately, weaving it into the visual imagery of Chilean society while exploring the spiritual dimensions of human life.

In Chile, as more women enter the workforce, they face the dual burden of professional responsibilities and domestic obligations, which also impact Christian and evangelical outreach.

Paula, a Christian and actress I interviewed in my research, emphasized how much more challenging it is to be a Christian woman in the arts. "In Chile, women must excel professionally just to be considered," she explained. "Technical and professional preparation is crucial, but as a woman, you might need to push even further."

And Carmen, a jazz singer and missionary, shared in the interview how she silently bore the weight of her work, ministry, and family responsibilities, hiding her exhaustion from everyone including her husband. "I didn't share how tired I was with anyone," she said. "It was tough–very sad times." Yet, her resilience in the face of these challenges is truly inspiring. These societal pressures are particularly exhausting for women, who are expected to maintain a constant image of moral virtue—adding an extra layer of expectation to their everyday lives.

In contrast to these societal demands, the loving response of Jesus: "Martha, Martha," is liberating and deeply humbling. He calls her by name with tenderness and care, inviting her to listen and rest. This call from Jesus, and the significant fact that this domestic scene is included in Holy Scripture, offers reassurance that He cares about our weariness and extends relief from the burdens we carry.

The tender, comforting call of Jesus speaking our name to break the invisible chains of culture and societal norms is a gracious invitation to find rest in Him. Even amid the daily social pressures of Latin American life–skillfully portrayed in JP's street artwork–Jesus extends the invitation to be free: to cry, to complain, to rest, and to rejoice in His loving presence. In His company, what once felt like a moral duty is transformed into a liberating and redemptive expression of love.

*******

Bible Reading: Luke 10:38–42

Juan Pablo Gatica (JP), Garden of Offerings, graffiti mural, Valparaiso, Chile, 2022.

JP is a Chilean urban artist whose work explores the spiritual dimensions of human life through a Latin American mestizo lens, bridging ancestral heritage with contemporary urban realities. Deaf since childhood, he creates contemplative and intimate images that evoke both silence and presence. In contrast to a noisy, artificial world, he envisions poetic spaces shaped by “clay and silence.” JP has collaborated on urban mural projects not only across South America but also in Spain, France, and Portugal. His art centers on the “human portrait,” capturing not only physical gestures but also the dualities, inner strength, and cultural symbolism embedded in everyday life. Web page: https://jp.portfoliobox.net/bio

Jessica Rosales G., PhD in Intercultural Studies (Columbia International University). Jessica’s research explores how art and hospitality—key elements of Chilean cultural identity—shape evangelical outreach in urban contexts. Her work highlights both the opportunities and challenges evangelicals face as they engage with the aesthetic and social spheres. She has taught courses on Christianity, philosophy, and culture. Also, she manages a virtual platform dedicated to sharing Christian philosophical insights—particularly in art, culture, and philosophy—from a Neo-Calvinist perspective with the Spanish-speaking world. Website: www.neocalvinismo.com

%20(1).png)