This beautiful meditation on Christ’s sacrificial death combines many facets of the gospel, not only in what it portrays but how it portrays it, and even the circumstances of its creation.

Vittoria Colonna, for whom the drawing was made as a gift, was a wealthy aristocrat, on first name terms with the Holy Roman Emperor and the popes. She was also a well-known poet, and indeed the first female poet to have her works published in book form, albeit without her consent, the laws of copyright not being then what they are now.

In the later 1530s she and Michelangelo became close friends and were part of what we would call a Bible-study group. According to one of Michelangelo’s biographers, Francisco de Hollanda, they used to meet with a few others once a week at the church of San Silvestro al Quirinale in Rome to hear a sermon based on one of Paul’s letters, and then sit and talk, almost always on the subject of salvation by faith alone.1

This was during the 30-year window between 1517, when Luther published his 95 theses, and 1545, when the Council of Trent began to crystallise the direct hostility of the Roman Catholic Church towards the Reformation. During this time there were many within the Catholic Church in Italy, across all strata of society, who believed the basic Reformation doctrine that salvation could not be earned but had to be received as a gift by faith, and they continued to hope that the Church could be persuaded to see this truth and to resolve the schism with the Protestants.

It is clear from Michelangelo’s poetry and his correspondence with Colonna that, through her, he too came to believe and accept salvation by faith – and this came to be reflected not only in the subjects of drawings that he made for her, but in their very approach to this art.2

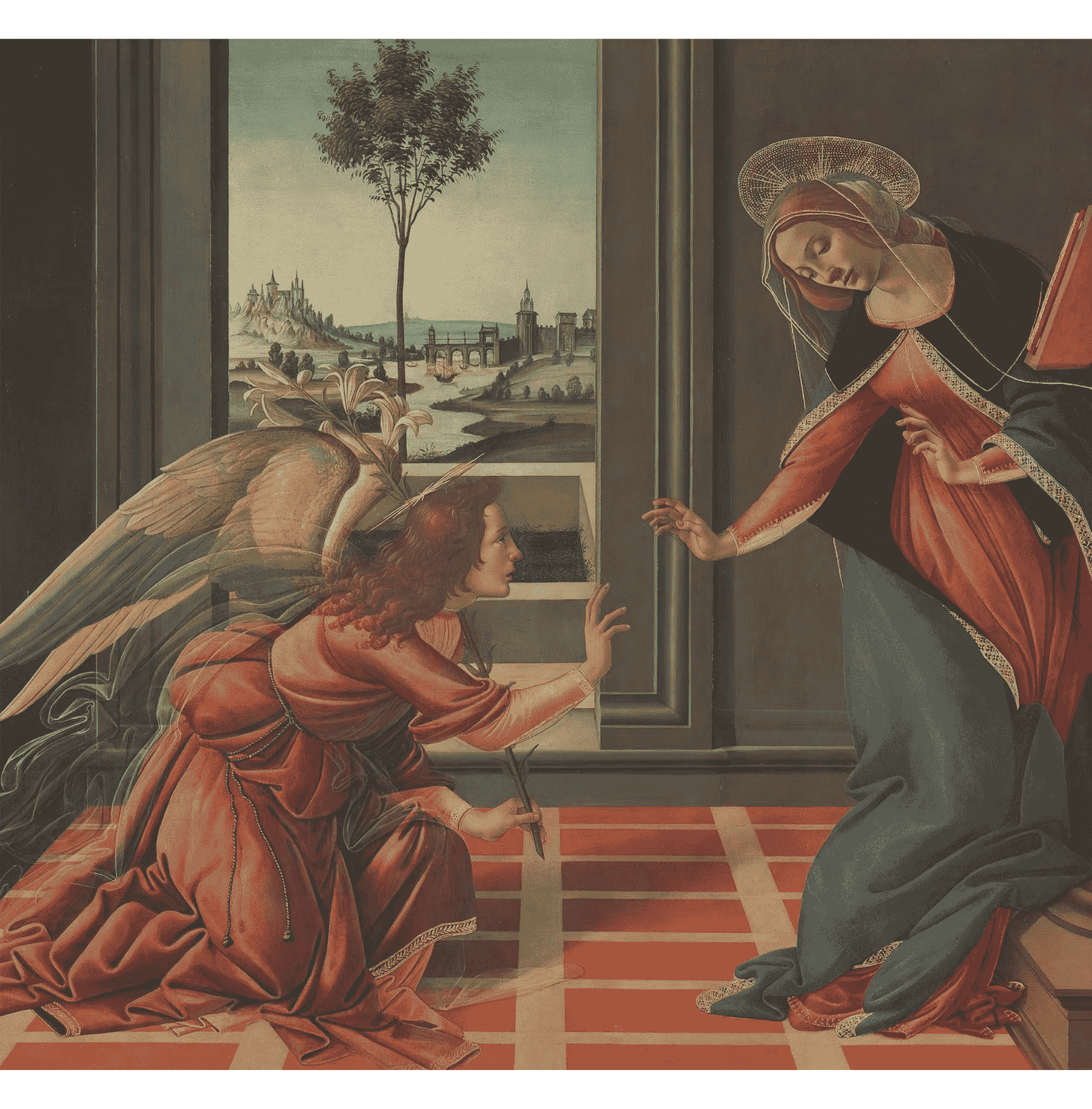

The drawing itself is a meditation on the sacrifice of Jesus. The presence of the angels supporting Jesus’ arms indicates that this is not meant as part of a narrative of the ‘descent from the cross’. Jesus is presented frontally, for us to worship and meditate on. As in all Michelangelo’s later Pietas, he is supported in an upright position, probably because the artist wanted to suggest that this is not just a dead body: there is power and hope within him. The marks of the crucifixion are only very lightly indicated: Michelangelo abhorred excessive detail, especially anything that would distract from the deeper significance of Jesus’ self-giving.

Mary the mother of Jesus continued to be a focal point of interest for Colonna, who at this period wrote an extended meditation on Mary’s thoughts as she looked on Jesus’ body. But, as in the Last Judgement which Michelangelo was then just finishing, he subtly rebalances the traditional Roman Catholic elevation of Mary. The positioning of Jesus between her legs is a poignant reminder of his birth, and her grief is rightly acknowledged. But in her upraised hands of prayer and, presumably, praise, she acknowledges the wisdom of God. And art-historians have observed that Jesus’ forefingers both point downwards into the earth, reminding us that his death is willed and willing: this is the direction he must take in order to be our saviour.3

This perhaps links to the words that Michelangelo has written on the cross. The line that runs vertically up the centre of the cross from the top of Mary’s head is a quotation from Dante, one of Michelangelo’s favourite authors: Non vi si pensa quanto sangue costa ("There they don't think of how much blood it costs"). This is taken from Canto 29 of the Paradiso, the third book of the Divine Comedy, in which Beatrice is lamenting how people do not appreciate the sacrifice of martyrs. Michelangelo takes this lament but applies it to the death of Jesus himself: transactional religion, which seeks to earn salvation by human means, misses the enormity of what God has done through the death of his Son, as the only sacrificial offering that can suffice for our sin.

The drawing is one of those now referred to as ‘presentation’ drawings. Artists’ drawings were already a focus of interest for art collectors, but these were means to an end, preparatory sketches for a sculpture or painting. ‘Presentation drawings’ were a new idea, an end in themselves. They were also, at least in Michelangelo’s case, created explicitly as gifts, and therefore separate from the art economy.

Alexander Nagel, in Michelangelo and the Reform of Art, explores how Michelangelo and Colonna were conscious of the nature of gifts.4 In their correspondence accompanying these gifts they underline that the inspiration for this new approach to art was the gospel itself: salvation has been given to me, irresistibly and unearned, and in response I can bless others with gifts that are beautiful, unearned, and unexpected.

But, as Michelangelo’s letters also underline, receiving a gift creates a sense of obligation, at the very least an obligation to value and pay attention to the gift. And this obligation is open-ended because the gift can never be repaid, because its value cannot be calculated. Those of us who know that our salvation cannot be earned still can be tempted to feel that we must do something post facto to merit it, or even to pay it back. But that would be a denial of the nature of grace. A gift must simply be received with thanks – and with acceptance of the obligation that comes with it.

**********

Notes

- See Alexander Nagel: Michelangelo and the Reform of Art (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p.171. Also, Francisco de Hollanda: Three dialogues on painting, trans. Charles Holroyd. In C. Holroyd, Michel Angelo Buonarroti, with translations of the Life of the Master by his Scholar, Ascanio Condivi, and Three Dialogues from the Portuguese by Francisco Hollanda, (London: Duckworth, 1903).

- See e.g. Herbert Von Einem, Michelangelo, trans. R. Taylor (London: Methuen, 1959), Ch. 11; Anthony Blunt, Artistic theory in Italy 1450-1600 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966), pp.64-81.

- This was first noted by Leo Steinberg, ’The metaphors of love and birth in Michelangelo’s Pietàs’ in Studies in erotic art, eds T. Bowie and C. Christenson (New York: Basic Books, 1970), p.267; and picked up by Alexander Nagel in Michelangelo and the Reform of Art, p. 185.

- Nagel, op.cit., pp. 170ff. See also his ‘Gifts for Michelangelo and Vittoria Colonna’, Art Bulletin 79:4 (December 1997), pp. 647–68.

Michelangelo Buonarroti: Pietà, 1538–1544, black chalk on cardboard, 28.9 cm × 18.9 cm.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor, painter, architect and poet. He is generally considered one of the greatest artists ever. He worked in Florence and Rome. As a student in the household of Lorenzo de' Medici Michelangelo met some of the greatest thinkers and artists of his days. In 1496 he moved to Rome, where one of his first major assignments was the now well-known Pietà in St Peter's Basilica. Back in Florence Michelangelo created several other masterpieces, including the David (1501-1504). Pope Julius II commissioned him to decorate the ceiling in the Sistine Chapel (1508-12). The frescoes depict prophets, sibyls and scenes from Genesis, translating from sculpture into painting Michelangelo's preference for strong, muscular figures. He returned to the Sistine Chapel in 1536 to begin the huge Last Judgment on the altar wall, finishing the work in 1541. In 1547 he was unwillingly put in charge of the rebuilding of St Peter's, and had a decisive influence over its final design. Michelangelo died in Rome in 1564. He is buried in the church of Santa Croce in Florence.

Nigel Halliday is a British freelance art historian, lecturer and teacher. He studied History of Art at Cambridge University and the Courtauld Institute, London. He teaches the whole canon of Western art from Giotto onwards, but his main interests have been nineteenth- and twentieth-century art. He also has particular interest in Michelangelo and Rembrandt and the influence of Protestant belief on their work. He is a Research Fellow of the Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge, England. www.nigelhalliday.org

%20(1).png)